When Tina Met Harvey

The Fine Print’s first-ever podcast revisits Talk, the last great magazine launch of the 20th century, born of the unlikely pairing of star editor Tina Brown and blustering film mogul Harvey Weinstein

On the debut episode of The Fine Print’s new podcast, available on Spotify, Apple, or wherever you like to get your podcasts, where we read a vintage magazine with a modern editor, we dissect Tina Brown’s premiere issue of Talk with Lux editor-in-chief Sarah Leonard, along with interviews with Brown and former Talk assistants, including New York’s Rebecca Traister, who recount the story of its creation and implosion. A transcript with bonus interview material, is available here.

Today, Talk is remembered less for its overstuffed first issue, or any of those that followed, than for its August 1999 launch party on Liberty Island. “I think of it now as like the Ship of Fools,” said Tina Brown, who partnered with Harvey Weinstein at the apogee of his Miramax powers to create what will probably be history’s last grand glossy launch. “The barge sailing up to Liberty Island and disgorging Madonna and Salman Rushdie and Demi Moore and Joan Didion. It was like my literary world and Harvey’s crazy celebrity world, and it was just amazing,” she told The Fine Print in our new podcast. “We had a firework display, which then I had George Plimpton do the narration.” An elegiac feeling pervaded even amidst the jubilation. “On the way back, I was on the last barge with Helen Mirren and Natasha Redgrave with Liam Neeson,” Brown recalled. “As we passed the Twin Towers, there was a huge gush of waves that just soaked us from beginning to end and we all sort of laughed. And I sometimes think about it because that was like the end of the 20th century.”

On July 9, 1998, the front page of The New York Times announced that Brown, then the editor of The New Yorker after reviving Vanity Fair, was leaving to start a new venture with Weinstein and Hearst Magazines, her first attempt at building a major magazine from scratch. The Times report cited “months of rumors of growing tension” between Brown and Condé Nast over The New Yorker’s “unprofitability,” but Brown told The Fine Print the reason she decamped S.I. Newhouse’s publishing empire after 18 years — the only real employer she’d ever known — was a feeling that her ambitions were being stymied.

Brown had pitched Newhouse on the idea of turning The New Yorker into an expansive brand, encompassing a magazine, book publishing, film production, and a radio show, but he turned her down flat. “Excuse me, it was the best idea you could possibly have had. It was the right thing to do, right? I was 20 years ahead of my time, let’s face it. But he didn’t like it and didn’t want to do it,” she recalled. “He actually said the words to me, which still gall my soul: ‘Stick to your knitting,’ he said. ‘You’re a magazine editor, edit a magazine.’ So this kind of boiled away inside me, and, just as I’m sitting there, boiling away, I go to a dinner and there’s Harvey Weinstein and he’s my dinner partner. He absolutely loves The New Yorker and everything I’ve done. He keeps telling me he wants me to go work for him.”

Weinstein promised to give Brown everything she desired. “Harvey just came at me like a barrel of bricks, and said, ‘Come and do a new magazine with me. You will have a book company, you will have a production arm, you will have any synergy you can name and a magazine,” Brown said. “It was what I had been dreaming of, right? So, that’s why I said yes, and that’s why I left.” The dream didn’t last long. “From the day I signed that contract, everything changed,” she said. “I knew from the moment I had my first meeting at Miramax downtown in that terrible dingy office that I’d made a terrible mistake. Because Harvey convenes the first meeting with his staff, his two or three key executives, that terrible blue sofa in that room which I think of as the Plymouth Rock of the #MeToo movement, and he starts hollering.”

Worse, she soon understood that Weinstein thought of himself as Talk’s true editor-in-chief. “He had all of these ideas. Some of them were quite good, but some of them were just loony, because they were just ideas that couldn’t be done. He was always saying things like, ‘Let’s rent an aircraft hangar and bring in Tom Cruise and photograph him with Richard Avedon.’ It was all these huge ideas, but at the same time there was never any budget for any of it. So that also completely rattled me, because I’d always have complete editorial control with Si. I didn’t have this marauding mad person coming in with these massively ridiculous ideas, and then having to fight them off.”

Brown also quickly realized Weinstein hoped to use the magazine to control how he was portrayed in other publications. “As he roamed around town, every gossip columnist who was about to do a bad story, he would say, ‘You need to have a contract with Talk magazine, I want you to go and see Tina, because I’m going to tell her to hire you, and we’re going to do a great piece,’” she said. “I’d hear from these really cheesy second-string gossip columnists all the time, who had been told they were going to have a writing contract. And there was just no way in the world that I was going to assign them even a diary item, let alone a contract.”

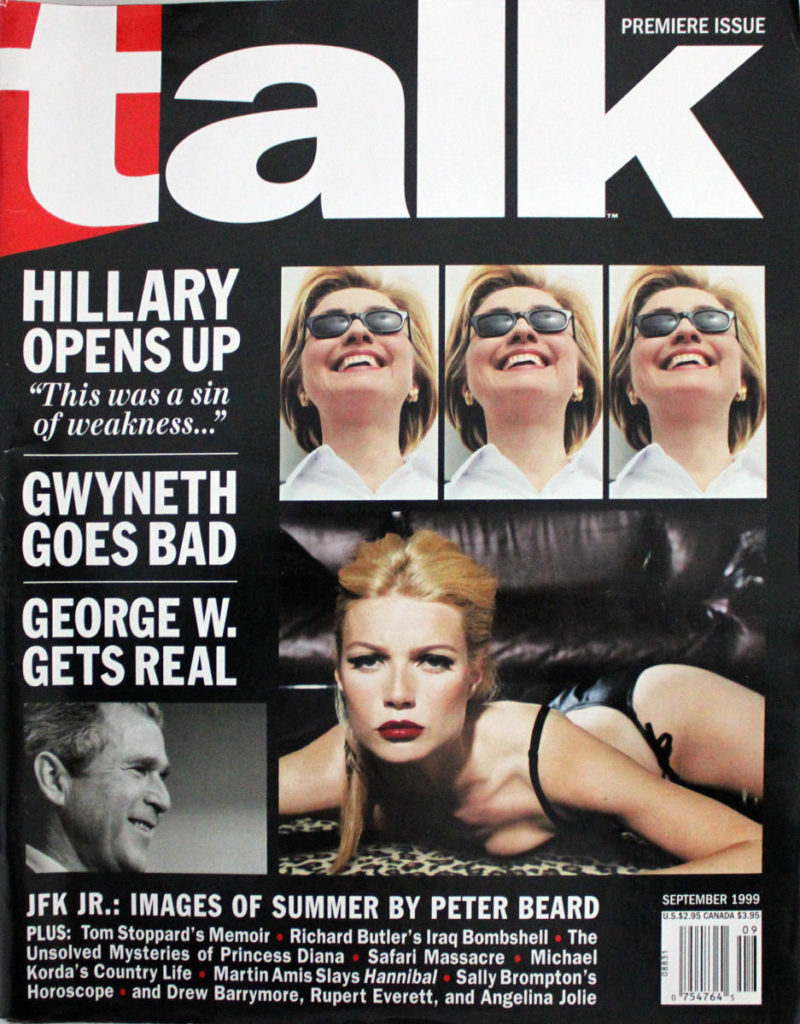

The cover of the first issue of Talk featured a profile of George W. Bush on the 2000 campaign trail by a young Tucker Carlson, Hillary Clinton talking about Monica Lewinsky, Tom Stoppard discovering that he’s Jewish, a spread of childhood photos of JFK Jr. published just after his death, and — this one was a top priority for Weinstein — Gwyneth Paltrow, the star of his Oscar-winning Shakespeare in Love, posing for very uncomfortable looking S&M-style photos.

“To be clear, that was not something she wanted to do. He was her godfather, and he definitely stepped in. That was a tumultuous conversation. She really, from what I understood, was pushed into that, specifically the a la Barbarella style,” said Alicia Clark, the former assistant to Talk’s publisher Ron Galotti, himself a paragon of the era’s hyper-masculinity and the inspiration for Sex and the City’s Mr. Big “But it wasn’t very public at the time. Nobody really understood that he controlled her to that level.”

Rebecca Traister, who was an assistant at Talk after working at Miramax and for Harvey Keitel and has since become a preeminent writer on gender and sexual politics at New York magazine, spread the blame for the magazine’s less progressive elements more broadly. “I remember conversations about feminism that took place at that magazine that were, especially coming from the top down, pretty anti-feminist. Like ‘feminism isn’t cool’ — directly. Which, I hasten to say, it was not cool,” she said. “The post-second-wave backlash that lasted through the ’80s and the ’90s — certainly, already, within the media, there was like a zine culture and a riot grrrl culture in the ’90s that existed on the margins, but it had not extended into mainstream glossy journalism.”

“At that time, feminism was actually uncool,” Brown said, “although much of what I published was by very strong women about very strong women. That’s the ephemera of magazines is that they’re a mirror of their times. It’s why magazines are interesting to look back on, it’s like this was the zeitgeist of that moment.”

Talk folded in 2002, a victim of the economic downturn that swept through media after the post-9/11 recession and the dot-com bust, after losing an estimated $55 million. More than 100 people lost their jobs. “I’m not really trying to blame the downfall of journalism on Talk magazine,” Traister said. “I certainly wouldn’t ever do that. But it was an example of taking cash and lighting it on fire just to see how pretty it would be when it burned.”

“The basic underpinnings of it were always roiling with this Harvey assault on my ways of working, his crazy temperamental outbursts, and the fact that he didn’t understand the magazine business at all,” Brown said.