Podcast Transcript: The Rise and Fall of Tina Brown’s Talk

We dissect the premiere issue of Talk magazine, Tina Brown’s ill-fated collaboration with Harvey Weinstein, featuring a young Tucker Carlson profiling George W. Bush, Hillary Clinton talking about Monica Lewinsky, some very uncomfortable-looking Gwyneth Paltrow photos, and so much more. Lux editor-in-chief Sarah Leonard joins as our inaugural editor-critic and the magazine’s former staff, including Tina Brown and Rebecca Traister, recount the story of the issue’s creation.

Listen to this podcast episode on Spotify, Apple, or wherever you like to get your podcasts. Bonus material is marked in purple.

Rebecca Traister: I have not ever had, and I don’t think there will be again, a tour of what was the ’80s, ’90s Condé Nast world, The Devil Wears Prada world. Talk was my greatest exposure to that — you take car services everywhere, and you have lunch out at Michael’s or Café des Artistes every day, and you expense your cheese and cocktails for when you have your famous people over for your dinners, right? Like, those were the expense reports I was doing. And you expense the massages. I didn’t know how unusual it was at the time. In my career in journalism since, I look back and I just shake my head, and I’m like, What? Can those memories I have be real? Was that what people were doing with money? Because it’s so antithetical to everything that’s happened to the industry since.”

The Fine Print: Part of the reason I’m interested in Talk here is that it does feel sort of like the last high watermark before everything starts to recede.

Traister: Right. And I think there are questions about, is it coincidental that it was the last high watermark? I mean, I’m not really trying to blame the downfall of journalism on Talk magazine. I certainly wouldn’t ever do that. But it was an example of taking cash and lighting it on fire just to see how pretty it would be when it burned.

Hi, my name’s Andrew Fedorov and I’m a reporter at The Fine Print, a newsletter covering the media industry. This is our podcast, where we read an issue of a vintage magazine with a modern editor and hear from the people who worked on the issue. For a transcript with photos and bonus interview material, and for media reporting like our interview with Fran Lebowitz about the magazines in and out of her life, our elegy for The New Yorker‘s Goings On About Town section, write-ups of lots of New York media parties, and our continuing series on media nepotism, subscribe to The Fine Print at thefineprintnyc.com. Our first episode is about Talk magazine’s September 1999 premiere issue. The other voice you heard was Rebecca Traister, who was an assistant at Talk in the late ’90s and is today a features writer at New York magazine. In July of 1998, she read on the front page of The New York Times — above the fold — that Tina Brown, the editor who had previously revived Vanity Fair and The New Yorker, was leaving The New Yorker to start a new magazine with Harvey Weinstein and Hearst.

It was Brown’s first attempt at building a major magazine from scratch. The first issue, which the staff put together over the course of a year, was a showcase of her wide-ranging sensibility. It featured a profile of George W. Bush on the 2000 campaign trail by a young Tucker Carlson, Hillary Clinton talking about Monica Lewinsky, Tom Stoppard discovering that he’s Jewish, Martin Amis taking on quote “Snobbo Sadist” Hannibal Lecter, a spread of childhood photos of JFK Jr. published just after his death, and Gwyneth Paltrow posing for very uncomfortable looking photos — this was a Harvey Weinstein magazine, after all.

Talk folded in 2002, having amassed a circulation of 670,000, and lost an estimated $55 million of its backers’ money.

“She burned through the money. I love that about her. She wasn’t afraid to do what she wanted to do. As much as she could, she pushed,” said Alicia Clark, former assistant to Talk’s publisher. “You can’t put forth that facade and not have the money behind you and have those fabulous interactions and coverage and access. And she knew it.”

Today, it’s remembered less for its jam-packed, overstuffed first issue, or any of those that followed, than for its launch party. I still hear about that party all the time while out reporting for The Fine Print. Media types of a certain age bring it up as the quintessential magazine party, the last great flowering before the industry’s unreversed decline. So, I had to ask Traister…

The Fine Print: Were you at the party?

Traister: Yeah, I was.

The Fine Print: What do you remember about it? Is it as opulent as everyone says?

Traister: It was bananas. Bananas! It was Liberty Island. I wasn’t at the party like, woohoo, having a good time. I think I was working, checking people in on the Battery Park side. And finally the guests had come through and we were able to go over to the party. So I got there probably halfway through, in fairness. Yes, it was opulent. And Rudy Giuliani had made a big deal about it, and so it was a tabloid thing and a New York tabloid thing in an era where that really meant something. You have to remember, this is pre-Gawker. It’s not pre-internet, but it kind of is pre-internet. It’s pre-blogs, so to speak. That was a word that I learned a couple years later when I was working at the Observer. So the tabloids really ran the game in New York City media, and they had fixated on the Talk magazine launch party.

Saffian: It felt like something big. I mean, I know this happens, and it’s happened at other publications I’ve worked for where you feel like it’s the center of the universe, but it felt like everyone is talking about this and I’m here.

That’s Sarah Saffian, once a reporter-researcher at Talk.

Saffian: There was a little of enjoying grumbling about, “Oh yeah, I work at Talk, it’s really crazy.” People were like, “Oh, my God, what’s that like?” And curious about “How is it in there?” It felt like the whole city was abuzz about the party, this magazine, Tina Brown. I just really felt like I was at the center of what everybody was talking about. It feels like the most important thing when you’re there and it was a spectacle, the way the magazine kind of felt like a spectacle.

Clark: It was over the top. This was every celebrity you’ve ever seen, from Madonna to Christopher Reeve. It was everybody. Every public person, everybody who owned restaurants, everyone who owned magazines, everyone who owned movies, any actors. I mean, my friends were making out with celebrities. It was just wild.

This is Alicia Clark, formerly the assistant to Talk’s publisher.

Clark: There were picnic blankets and beautiful lights glowing overhead as you sat looking at the Statue of Liberty with fireworks going off.

The magazine in its mesh packet, as party guests received it.

The Fine Print: I think a little bit of my thesis for this episode is that the Talk party has overshadowed the actual content of the magazine.

Brown: Well, I know. In fact, the great David Brown once said to me never give a party that’s better than the magazine, but actually, the magazine was a hell of a lot better than the party is the truth. But the party did become an iconic party.

That, of course, is the unmistakable voice of Tina Brown. I have to say our call didn’t have the best audio quality, but it’s very worth it to hear one of the geniuses of magazine editing describe the conception of a single issue in extreme detail.

Brown: People kind of imagined that the reason it began was some mad expression of who we were, but actually it all began because Rudy Giuliani banned us from using the Brooklyn Navy Yard when he found, pettily, that his competitor in the senator’s race was Hillary Clinton and he did not want to see anything that publicized her. So he just said, “You’re not having the Brooklyn Navy Yard.” That petty, he was. So of course, being Harvey — one of the very, very few things one can say about Harvey in his favor — that that got his dander up. He said, “You’re gonna have to just find a federal site. We’ll do it bigger, bigger, bigger.” I think it was Gabé Doppelt who said to me, “Why don’t we do it on Liberty Island?” And I then went to see Robert Isabell, who was the great party entrepreneur of all time, with whom I did many a wonderful party. He was the visual genius behind Studio 54. So Robert said, “I’ve always wanted to do a party on Liberty Island.” I said, “The problem is there’s no electricity at all. It’s just complete darkness, even if we get the place.” He said, “We’ll do Chinese lanterns. It’s going to be phenomenal. No one will be able to see anything, but there’ll be Chinese lanterns.” And then he starts to sketch this extravagance, it’s going to be so fabulous. And then it was like, well, how are we going to get the ferries over there? Every single thing. We found a way to get around the whole problem of doing it on Liberty Island. And then, I invited a huge mix of amazing people and then Harvey fed into that mix some of his amazing people. And so that’s how we ended up with, I think of it now as like the Ship of Fools. But I mean, the barge sailing up to Liberty Island and disgorging Madonna and Salman Rushdie and Demi Moore and Joan Didion. So it was like my literary world and Harvey’s crazy celebrity world and it was just amazing. We had a firework display, which then I had George Plimpton do the narration. It just built and built until we had every element of this thing. It was just so amazing. This was the party where Salman Rushdie under a Chinese lantern met Padma Lakshmi for the first time. The editor of The New York Times was up at the top of Liberty with Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne. And on the way back, I was on the last barge with Helen Mirren and Natasha Redgrave with Liam Neeson. And we were sort of sailing out on that last barge and as we passed the Twin Towers, there was a huge gush of waves, that just soaked us from beginning to end and we all sort of laughed. And I sometimes think about it, because that was like the end of the 20th century. Within a year, the Twin Towers were down, everything changed. So in a way, I think people think of the Talk party as a sort of end of a moment and an end of an era. It was a late end of the 20th century.

Margaret Dawson, who was Tina Brown’s assistant at Talk, poked some holes in all this nostalgia. “Are you serious? Come on,” she exclaimed. “I’m sorry, not to trash it, but I’m sure there are even more fun parties than that. I feel like a bunch of media people who aren’t used to a certain kind of glamor — because literary parties, obviously, can be very starry and very high profile as well, but when you add Hollywood, perhaps, maybe that’s where it’s a little bit different for certain people who attended it, but I certainly am surprised when I’m like the party.” Did she feel she’d been to better parties? “No, for sure. I mean, it’s not my world at all. But I’m just like, guys really? Okay. I just feel like wouldn’t a Fashion Week party outdo that? Or certainly the Met Gala?”

To help us deconstruct the premiere issue of Talk, we invited Sarah Leonard, editor-in-chief of Lux, the glossy magazine of socialist feminism that puts a 21st century spin on the tradition Talk comes out of.

The Fine Print: How did you first get into Talk?

Leonard: Well, I love Tina Brown’s Vanity Fair Diaries. It is the most entertaining book about media. It’s just piles of gossip. But it’s also a really good rendering of how you put a magazine together internally. She’s this sort of whirlwind and extremely excited about making an excellent magazine. She loves magazines. Vanity Fair of that era was kind of brilliant. She talks a lot about the mix of entertainment and glamor and intellectual work and reporting that all together creates a sensibility that was Vanity Fair, or was Talk. When I put together issues of Lux, I often have that in the back of my head. Because to me, what makes a good magazine is not just, oh, this issue had this one really good article, it’s that X was next to Y. It’s in the juxtaposition that you get a sensibility and I think she’s kind of a genius at that. I really loved her description of putting together Vanity Fair, which is a magazine, of course, that does not particularly overlap with my politics, or my worldview, but I still think is brilliantly put together. So I was looking at how she had put together other things, and I was curious about Talk. Of course, she did Talk with Harvey Weinstein, so that was back in the news. So I bought the inaugural issue of Talk off of eBay, as I buy many old magazines, like a magazine nerd. And then I actually started reading it. I had it by my bed. You know, it’s from 1999, it’s not really breaking news, and I still found it compelling. That’s a sign of a pretty good magazine, you know?

The Fine Print: Totally. Within Tina Brown’s career, it’s sort of the magazine that she got to make from scratch. I mean, The Daily Beast kind of counts, but that’s not a magazine, right?

“Tina was pretty amazing when it came to taking institutions like Vanity Fair and The New Yorker — really, I would say, she created Vanity Fair, she recreated The New Yorker — and breathing new life into them. But I think what Talk showed was that it is just a different thing to create something from scratch. And it’s not that Tina didn’t have a vision for that. She did, up to a point, but I think that she was kind of unmoored in a way that wasn’t good for Tina or me or anybody else,” said a former Talk staffer. “Tina is this churning generator of ideas, constantly pushing for change, constantly pushing to make things better — not everybody sees it that way. When she had Vanity Fair or The New Yorker as existing things, she was pushing against something. I think not having something to push against is why — it’s almost like if you take that sense of creation, recreation, less positively chaos, out of the context of something grounded, then it’s almost just pure chaos.”

Leonard: You know, Talk is funny because it looks sort of tabloidy. The first magazine that Tina Brown edited herself was Tatler in the UK. I mean, she can have a tabloidy sensibility. But you do get a sense of her really breaking free from her seven years at The New Yorker, which was much more refined in a way, and there was hardly any photography. I mean, her New Yorker had one photographer. Was it [Richard] Avedon?

The Fine Print: It was Avedon. It was first Avedon and then Max Vadukul took over for him.

Leonard: Yeah. So, you know, that’s a very streamlined sensibility. And this issue has a wide range of the best photographers. It clearly takes up from Vanity Fair; people who photographed for Vanity Fair also photographed for Talk. I think there’s some controversy over who felt that they could betray Condé Nast by doing that, but she really has the best in here. And so you get that sort of entertainment combined with the hard news element of Vanity Fair, but it feels, certainly in its design, a little bit more rough and tumble than Vanity Fair does. The cover has “Gwyneth Goes Bad.” It’s like Gwyneth Paltrow in bondagewear, hilariously directly under Hillary Clinton.

The Fine Print: Three Hillary Clintons.

Leonard: Three Hillary Clintons next to the headline “Hillary Opens Up: ‘This was a sin of weakness.’” And then “Gwyneth Goes Bad,” and then “George W. Gets Real.” The requisite JFK photographs seem to follow from Vanity Fair, as well as some stuff about the unsolved mysteries of Princess Diana. I mean, there’s a lot in common with Vanity Fair. You know, the safari massacre. There’s always some super-pulpy but also well reported story of drama, often stories about Africa in a way that feels very safari-ish, this kind of gross thing that magazines did then, of trying to create a sort of exoticism for their readers in their pages through these stories that were not actually foreign affairs stories, but stories of the life and death of some dramatic individual. I mean, Vanity Fair tipped over into — the way they created some real charge in their pages was often by profiling in a glamorous way, and they would say a critical way, but it was undeniably often glamorous, dictators or often their wives. So like an Imelda Marcos story, and post-Tina Brown that absolutely continued in Vanity Fair. I remember, this was not her era, this was much, much more recent, but you know, a story in Vanity Fair featuring Eric Prince hanging out of a helicopter, doing his mercenary worst, but looking very, very cool. And that’s like the dark side of this sort of sensibility. But I do think that Talk is a little scrappier and more aggressive-feeling than Vanity Fair, which just feels a little more highbrow.

Brown: Talk was really birthed by a long-running vision I had when I was editor-in-chief of The New Yorker, from ’92 through when I was asked to do Talk, which was, I think, ’98. I felt strongly that The New Yorker needed to become more than a magazine. I thought it should be a magazine, plus a book company, plus a film production company, and a radio show, which today, of course, would be podcasts, and I tried to persuade Si Newhouse, the chairman of Condé Nast, that The New Yorker now should be what I called the HBO of print. Excuse me, it was the best idea you could possibly have had. It was the right thing to do, right? I mean, I was 20 years ahead of my time, let’s face it. But he didn’t like it and didn’t want to do it. And he kept saying, “no, no, no.” He actually said the words to me, which still gall my soul. “Stick to your knitting,” he said. “You’re a magazine editor, edit a magazine.” So this kind of boiled away inside me, and, just as I’m sitting there, boiling away, I go to a dinner and there’s Harvey Weinstein and he’s my dinner partner, and he absolutely loves The New Yorker and everything I’ve done. He keeps telling me he wants me to go work for him. Now pause, okay, rewind. I know people will be thinking, “Oh, my God, how could she?” But at that moment, we’re talking about the Harvey Weinstein of The English Patient, of My Beautiful Laundrette, of all of these great movies. He was about to release Shakespeare in Love. Harvey was like the pinnacle of quality content, essentially. To me, Harvey was like music to my ears. So anyway, then my contract comes up. Si offers me a really excellent deal, which I found the other day in a drawer. What was I thinking, giving up that deal? But I was sort of havering and havering and Harvey just came at me like a barrel of bricks, and said, “Come and do a new magazine with me. You will have a book company, you will have a production arm, you will have any synergy you can name and a magazine.” It was what I had been dreaming of, right? So, that’s why I said yes, and that’s why I left. I’d had 18 years working for Si Newhouse. I was 26 or something when he bought Tatler, or 27. So he was the only boss I’d ever known and Condé Nast was the only place I’d actually ever worked. But I really wanted to be an “entrepreneur,” because at that time, don’t forget, it was the dot-com explosion. That was the other piece of the reason I left — everyone around me was suddenly an entrepreneur, right? And the other problem with Condé Nast was that you got extremely well paid, but you were never going to have any piece of anything. It was just a family-owned company. And that’s why Si overpaid everybody, because he could never offer anybody any kind of piece of the company. I knew it was a finite situation and I wanted to have a piece. So that was another very attractive piece of it to me. Si was very, very upset about my leaving, I mean, hugely upset. And he vowed that he couldn’t possibly help me in any way. In fact, his editors were empowered to spend as much money as they wanted in making sure that no writer or photographer could ever write for Talk or photograph for Talk and also be part of Condé Nast. So it put a lot of difficulties in my way.

When Brown left Condé Nast, she took with her Ron Galotti, the star publisher of Vogue and the inspiration for Sex and the City’s primary love interest, Mr. Big. As Galotti admitted to Jay McInerny, before getting to Vogue he’d run a brothel in the Philippines. Alicia Clark, Galotti’s assistant at Talk, had previously been an assistant at Weinstein’s Miramax. She watched as her new boss realized the scope of his new challenge.

The Fine Print: Did you have much sense of his reputation going in?

Clark: I knew that he was famed for being the basis of Mr. Big. And I knew that he was a big persona who dated a lot of supermodels. But it was a growth time for him. I think there were several times in Ron’s life where he really was pushed to grow and that was certainly one of them. Because he’d always been the bigwig, I think, over at Condé. For him to meet someone like Harvey who had such a reign over that company and even Disney at the time, it was a whole new world for him. And probably a little sobering.

Clark’s path to Talk was as singular as Galotti’s. “I had written my senior dissertation on Harvey Weinstein and I wanted to be at Miramax. I loved his movies. It was a very different experience once we joined the team, you learn a lot about what goes on on the inside. But it was still an exciting time and I was thrilled to be there,” she said. “And they said, ‘Hey, we need somebody up at 57th Street at the Carnegie Hall Tower,’ which was 60 floors above Central Park. I had a leather couch and a computer and I was 22 years old. And I shared an office with Tucker Carlson. It was wild.”

Brown: Condé Nast had a double reason to be furious with me. Not only had I left, but I also took their best advertising sales guy. Ron and I were like these two orphans racketing about town without an office. We had to start everything from scratch. We learned as we went along. I mean, I’d never been an entrepreneur in my life; nor had Ron, as a matter of fact. Doing stuff without the basis of a company is the most daunting thing.

Margaret Dawson, Tina Brown’s assistant at Talk, felt that Galotti had what it took to survive the new environment.

Dawson: I feel like if you’d taken away the Harvey of it, you would probably say Ron was the most aggressive person; I mean there’s a reason why he was nicknamed Mr. Big. But he was never — he wasn’t toxic the way that Harvey was.

Brown: Within day one, Harvey Weinstein, the ebullient, bon vivant, generous, come work for me, it’s all going to be marvelous — it was like Jekyll and Hyde. From the day I signed that contract, everything changed. I knew from the moment I had my first meeting at Miramax downtown in that terrible dingy office that I’d made a terrible mistake. Because Harvey convenes the first meeting with his staff, his two or three key executives, and that terrible blue sofa in that room which I think of as the Plymouth Rock of the #MeToo movement. And he starts hollering. Within five minutes, he’s so incredibly abusive to his staff, I can’t believe it. He turns to one of his key executives and says, “Fucking sit up.” Don’t forget, I’d only ever worked for Si Newhouse, right? Who was the most courteous, mousy kind of guy. He’s like, “What the fuck are you doing? That’s a stupid idea.” I was taken aback. I thought, Oh, my God, this guy’s gonna get up and slam the door and say “I quit.” No, he just went on sitting there. And I realized with mounting horror that this was [Harvey’s] MO. This is how he treated people. And then immediately, I came to realize that he really saw himself as the editor-in-chief of Talk. He had all of these ideas. Some of them were quite good, but some of them were just loony, because they were just ideas that couldn’t be done. I mean, he was always saying things like, Let’s rent an aircraft hangar and bring in Tom Cruise and photograph him with Richard Avedon. I mean, it was all these huge ideas, but at the same time there was never any budget for any of it. So that also completely rattled me, because I’d always have complete editorial control with Si. I didn’t have this marauding mad person coming in with these massively ridiculous ideas, and then having to fight them off.

Dawson: It’s no secret Harvey was completely controlling of all of his projects. So it’s interesting — the trial and all of the coverage of him, all of it sounds extremely familiar. This micromanaging, this anger, that’s a lot to deal with compared to the Newhouse family and Condé Nast and a very set way of doing things for a long time, within which Tina was able to spread her wings creatively. Very different dynamic under an upstart.

Alicia Clark, Ron Galloti’s assistant, saw a lot of that too.

Clark: That was the luxury of it and that was the problem of it all. Harvey had way too much influence over it. Harvey was tired of being told by Graydon Carter that he couldn’t get his stars on his magazines. This was his vehicle. Like, “Screw you all. I’m Harvey, I’m going to make my own magazine, I’m gonna push my own people, I don’t need to ask for permission anymore.” Absolutely, there were phone calls coming in hourly about how to and how not to portray certain people.

Brown: It also became clear to me that he saw one of the great assets of having Talk magazine would be that as he roamed around town, every gossip columnist who was about to do a bad story, he would say, “You need to have a contract with Talk magazine, I want you to go and see Tina, because I’m going to tell her to hire you, and we’re going to do a great piece.” And I’d hear from these really cheesy second-string gossip columnists all the time who had been told they were going to have a writing contract. And there was just no way in the world that I was going to assign them even a diary item, let alone a contract. And, again, it was like, where’s this budget coming from that you keep castigating me about? It became so destabilizing.

But this was a time when that sort of behavior from powerful men was not only accepted as normal, but often given a gloss of necessity. For Rebecca Traister, it was an exposure to the kind of sexual politics she’s written about since.

Traister: When I was a young person working within the Miramax orbit, a lot of the stories that were passed around between people were about what we would later come to understand as and be able to cogently frame as Harvey’s sexual predation, but that at the time, were told as, “Well, that person slept with Harvey to get a role.” That was an active point of conversation amongst young people who paid attention to Miramax or worked for Miramax. It was understood. And it was also understood that you wanted to avoid his bad temper. Nobody was like, “ah, Harvey, what a nice guy.” People were scared of him, in awe of him. I should also say that it was not long after that that you did begin to hear scarier stories. It wasn’t from then to #MeToo. There were years in which people tried really, really hard to report on it, until Jodi (Kantor] and Megan [Twohey] and Ronan [Farrow] all did. But I’m saying that when I first got to Talk, he was a figure who loomed large, who fit a certain kind of role that yes, was completely associated with what we would now describe as abusive, harassing, assaulting behavior, both sexualized — I mean, later, much later in my life, Harvey screamed at me in public and assaulted my colleague without it being sexualized. That was later when I was at the Observer. But the imposing, angry, brutal figure he cut was, in my first encounters with it, definitely simply understood as the embodiment of a certain kind of power and authority. And one that was bringing glory to New York City as a filming destination. Harvey was going to win Oscars. He was making great movies, and apparently, you had to do that by brutalizing people.

Though Weinstein was overbearing and brutal in many ways, he gave Brown a free hand in choosing her staff. She filled the upper reaches of the masthead with people who’d been with her at Vanity Fair and The New Yorker like Gabé Doppelt, David Kuhn, and Howard Lalli. For the rank and file, she scoured New York’s independent publications.

Brown: I always say to people when they start new things, “You have to recognize when you are calling people, you’re calling as you.” When people go, “Oh, they were great. They know how to get celebrities. They were on the NBC Today Show.” I say you don’t understand. That’s not what I want to hear. Because if you say, “Hello, I’m from the Today Show,” you immediately can get somebody to pay attention to you. If you say I’m calling as me and I’m trying to persuade you to do this thing for this magazine or show that no one’s ever heard of yet, it’s a whole other proposition and you need a whole other level of scrappiness, seduction techniques, strategy, cunning, hustle. You are a different hire from someone who has already been in the sleek worlds of established media. We spent time trying to build that team with people who were that way. I got tremendous knockbacks from people who thought it sounded exciting, but weren’t going to leave their great places of comfort. So we had to find new people and we found amazing new people who ended up being the establishment of now. People like Sam Sifton, who was on a small, independent weekly, and now is the food baron of The New York Times, Jonathan Mahler, who was I think at The Forward newspaper and now of course is a major author with The New York Times, Danielle Mattoon, I can’t remember where Danielle came from, but for a long time, she then was culture editor of The New York Times. The Times basically took everybody from Talk magazine, Virginia Heffernan who became The New York Times TV critic.

On the other hand, much of the clerical staff, like Traister, were drawn from the Miramax orbit.

Traister: It was absolutely my first magazine job and I had no intention of becoming a journalist at the time. I think that’s really important to note. I did not go to journalism school, I did not think I was going to become a journalist. I did not have a goal of working at a magazine. I came to Talk after having worked as a personal assistant to an actor for a year or two, Harvey Keitel. And Harvey Keitel’s offices were in Tribeca, right across from the Tribeca Film Center, which was the home base of Miramax. I came to that Talk job entirely through my association, not directly with Harvey Weinstein, but with many other young people who worked for him. But what is true is that there was a raising of the fortunes of a generation of journalists, because Tina actively went out and picked a group of young people. For the group of young editors who were going to do the bulk of the assigning and editing of the stories, Tina went to what at the time were more independent publications. And I was an even younger person who had not come from anywhere that had anything to do with journalism, and I got to meet and befriend and hang out with these people. There was a tremendous mixing between the editors, the assistants, the fact checkers. There was a lot of mixing socially between the business side and the editorial side. It had some startup spirit, because it was starting up for so very long. And while there certainly was a big gulf between Tina and the rest of the editorial team, there was not a big power gulf or age gap between the editors and their assistants and researchers and fact checkers, and that permitted a degree of social mixing and fun and pleasure and getting to know each other. And in my case, selfishly, it also allowed people who were senior to me, but connected in the rest of journalism, to say, “Oh, Rebecca, maybe you should consider being a journalist.”

Traister ended up working for Keitel out of school because she wasn’t sure what else she could do. “I had a vague idea that I might want to work in movies. I had no movie-related talents or skills. This is bizarre to say, but I actually thought journalism was a far more glamorous job and that it would not be accessible to me. It never occurred to me,” she said. “Working as an assistant for Harvey Keitel was a very loose affair. In fact, I went and traveled with him to Italy for three months in the summer of ’98, I guess, where I lived in a set of houses with Harvey and his trainer and his acting coach and, at times, his daughter.”

As Brown gathered her team, she sketched out what her magazine would be. Alicia Clark, Galotti’s assistant then, remembered the inception of the name.

Clark: She wanted one word. She wanted power. She wanted inclusivity. She wanted to be progressive. She wanted it to be eye-catching. And if you remember, there was a video made. She’s talking about it, we always used to laugh at her signature line, and she goes, “Want to Talk. Need to Talk. Talk.” She loved the name. When we landed on it. She really drummed up excitement around it. “You want to Talk. You need to Talk. You must Talk. Talk!” Okay! She wanted some of the glamor, but she wanted the grit. She wanted the intellectual types, she wanted the iconicism, she wanted Patrick Demarchieler to photograph everything. She wanted Tom Stoppard as her head writer. It was different. It was over the top. She didn’t want a budget for certain.

A promotional mailer

For much of its gestation, the magazine existed as a series of mock-ups.

Traister: I walked out of Talk magazine with a ton of paper. And among the things that I have somewhere in my attic, they’re all in boxes — I don’t live in like a shrine to Talk magazine weirdly — but somewhere up there are these really stunning art mock-ups. I mean, I didn’t take anything huge. They were little, eight by eleven, I think, early cover concept ideas that are very beautiful. And they were being thrown out. And they were really early. They couldn’t have been more different from the Gwyneth, Hillary, where the cover wound up, or where it continued to go. These were sort of shocking images, somebody’s heart in somebody’s hand. They were startling photographs on the front.

Brown: At the time, I was completely obsessed with European news magazines like Stern and Paris Match. Those great news glossies of Europe, which don’t really exist here. Time and Newsweek were always small actual news magazines, whereas Paris Match or Stern are a really interesting combination of visual splash with news, current affairs with literary standards. And I thought, that’s what we need to have here. And there was a Dutch magazine of the ’70s, called Twen, which I became completely obsessed by, as I tend to do. Twen magazine in the ’70s was a great Dutch glossy magazine. And Nova magazine in England in the ’70s was another great magazine. Those are the magazines I wanted to do. That was my design concept. The two tenets were thinner, upscale newspaper. Size was big. Twen was a big magazine. It wasn’t like a Time or Newsweek, it was the size of Paris Match. And then it was going to be saddle-stitched like one of those news magazines. And the design, the typography had a kind of hip tabloid flavor to it. I mean, I really had this idea how I wanted it to look. And I adored the way the first magazine looked. I thought it looked so good and I thought it did everything it was supposed to do. And Harvey just hated it. I mean, he wanted it to be Vanity Fair. He immediately said, “Absolutely not. I don’t like your concept. We’re going to do glossy paper. We’re going to do a perfect bound magazine. You’re gonna have celebrities on the cover.” Why would I want to do Vanity Fair again, when I had done the best Vanity Fair imaginable at Condé Nast with everything great. I mean, I left Vanity Fair because I didn’t want to keep doing the celebrity stuff, and went to The New Yorker. I didn’t want celebrities on the cover, I wanted a multi-picture cover, like you have on Stern. And the first cover, for instance, has Hillary Clinton plus Gwyneth Paltrow plus George Bush, Jr., who was running for president, in these boxes. It was almost like a magazine version of a homepage, actually. And it looked great, I thought, really fresh and interesting. And it didn’t mean that you were dependent on one film star, which I was so bored with as an idea.

I asked Sarah Leonard, our editor-critic, about her familiarity with these antecedents.

The Fine Print: Have you ever picked up an issue of Paris Match?

Leonard: You know, I’ve never seen an issue of Paris Match from this era. I’ve seen Paris Match in our era. I think the first time I really looked at a copy of Paris Match was when [former Greek finance minister] Yanis Varoufakis ill-advisedly allowed himself and his wife to be photographed for Paris Match in the middle of trying to solve the Greek financial crisis. Not a great move. You know, it’s like pictures of their beautiful apartment, he’s playing piano, his wife is from a wealthy family, and famously, is perhaps the inspiration for Pulp’s song “Common People.” She did go to art school in the UK. So that was the first time I really had reason to look closely at an issue of Paris Match. I was covering the Greek crisis. I’m very Varoufakis-sympathetic. I think a lot of stuff he did during the Greek crisis people like to blame on him, but no one else was doing any better. But you never need to go in Paris Match. Just don’t do it. You never have to tweet, you never have to be photographed for Paris Match.

The Fine Print: But you did have to be photographed for Talk in ’99, I guess. What do you think of the cover design? Like if I saw this on a newsstand, maybe I would be intrigued. But I don’t know if my attention would be caught by anything.

Leonard: Yeah, it’s funny. Vanity Fair was famously appealing for its covers, which were often these gorgeous Annie Liebovitz celebrities or Helmut Newton shooting something a little bit creepy and controversial. They’re very, very striking photographs. And this is like this weird tabloidy thing where there’s no one good photograph on this cover. There are arguably three bad photographs and a lot of headlines. And I still love it. I have to say, I feel like I really love a magazine that is going to give me substantial information, you know, that there’s a reason to read, but that is also finding ways to appeal to my lowest sensibility. And I like a magazine that’s like a candy box. It’s like, “Ooh, I want to look at that. I want to look at this.” And this sort of does that. It’s like you have your politics, you have your celebrity. Even when the covers are trying to get you to read a couple of major political features, one on Hillary Clinton and one on George Bush, they are packaging them as personality stories. As an editor over the years, I’ve learned a lot from that, where a lot of the political writing we do in Lux is framed around a person. We use profiles to hopefully tell quite substantial political stories. And Talk is really great at focusing its political stories on dramatic individuals. The downside of that is you have a little bit of an access journalism project where the pieces can be heavy on compelling personal anecdotes and light on the political analysis. We can get into the political profiles, but I do think that that happens here. And you get a taste of like, when Tina Brown launched The Daily Beast, she talked a lot about how if you read The Daily Beast and you rolled up to a cocktail party that evening, you would know what was going on, you would have stuff to say. And one wonders, does that fucking matter? Like, I don’t know if that’s a good criteria. But you get a little bit of that in Talk, where like 100%, if you read this issue, you would roll up to a party with a lot of interesting things to say and entertaining anecdotes. And the question is, can that be married with really substantial reporting that makes a difference?

The Fine Print: Right. One of those things to say might be that George Bush seems like a nice guy.

Leonard: Yeah. I mean, there’s a lot to say about that profile. The number one thing being it was by Talk magazine contributing writer Tucker Carlson, which is very jarring to look back at now. In 1999, he was like a Republican moderate in a bowtie and he was writing this profile of George W. Bush, which is sort of trying to explain his everyman appeal. It’s about the 2000 election. And the impressive thing about the access journalism here is there are great quotes, there are great anecdotes, George W. Bush is just swearing up a storm constantly. But it does this sort of dance between this actually quite well written political portrait of this candidate — you get a real sense of his personality, it’s a very compelling read, it’s well done — and the sense that Tucker Carlson is doing some light propaganda here, in a style that would come to define him later. So his whole shtick is it seems like Bush doesn’t actually care if he’s ever president. He’s so confident in himself, it’s actually confusing to people why he even wants to be president. It’s like he just ended up here and he doesn’t need attention like other politicians need attention. It’s very flattering. You have Tucker Carlson manufacturing these fake acts of rebellion by wealthy people, basically. And it’s like, that’s his whole sensibility. That’s his sensibility today.

Most of Talk’s former staff had a hard time seeing that continuity. The feeling at the time was that Carlson was one of the tribe, a consummate media professional. Traister remembers others trying to mollify her outlier perturbation.

Traister: I remember being assured that Tucker was a good guy. I remember being assured that George Bush was a good guy, in kind of the same tone that I was assured that Tucker was. I was repelled by the holding up of George Bush as a regular guy. I was like, what now? I don’t want to make it seem as though I was mounting some deep political objection. I was just like, what? Why? And I remember having people say to me, “No, he’s pretty good.” That’s the vibe I remember, because I was distressed. It wouldn’t have mattered though. Who cares if I was distressed? I was an assistant there. But I do remember people saying to me, “No, no, it’s fine. Bush is actually pretty interesting. He’s a reasonable guy. And Tucker is funny.” There was a lot of affection in the office for Tucker. And Tucker Carlson’s prominence didn’t originate with Roger Ailes. Tucker was the favorite conservative guy of a lot of mainstream journalists and that was very evident at Talk magazine.

Margaret Dawson, then Brown’s assistant, was one of those who was shocked by who Carlson has become.

Dawson: I’m just amazed at the Tucker Carlson of it all. I’m like, what? When people see that they’re like, What? You used to? Who? What? Very different time. A lot of people don’t know that about him. They just know the Fox part of it. It’s not that it wasn’t always him, but my memory was very different of him. But it doesn’t mean that he can’t be both wanting to blow up the democracy and also a pretty good writer and a pretty good reporter.

Brown: Well, you know, I’m completely stunned because Tucker Carlson was such a fun, charming, clever member of the Talk band. We went together to the Republican Governors Conference; I went as his kind of date when George Bush was the chairman, I think it was. Working that room with Tucker was just the most incredible fun. I mean, he was wildly irreverent, he was very much a journalist, he was there to get great material and did. He was nothing like this grotesque, Göring-like figure that he’s become today. It’s one of those things of people just utterly changing over the years. I regarded Tucker as one of the greatest talents at Talk. He’s a very, very good stylist. I thought that he was Christopher Buckley-like, his tone, he had a great voice, he was funny as hell, very irreverent about the Republicans as well as getting great access. So to me, he was a star. I was very excited about having Tucker because I wanted some access to the Republican side, but with a really satirical eye. And he had that in those days. What happened in the meantime? I mean, I’m reading Michael Wolff at the moment and he still doesn’t really explain it.

“I had two political correspondents at Talk, whose names were Tucker Carlson and Jake Tapper,” Brown added.

For Sarah Leonard, the roots of Carlson’s current manifestation are apparent in the pages of Talk.

Leonard: I think if you look at the people in these pages, you see hints of this right wing flip that would happen in some parts of the establishment. You have very well-established writers. So you have Tucker Carlson and then you have someone like Walter Kirn, who’s in this issue, and their whole thing, the thing that makes their writing good and entertaining, is they like to be a little provocative. And they tend to be provocative in kind of shitty ways that are not so easily accepted now, and you can see how one way to respond to that is to join the Intellectual Dark Web or whatever and say that people are snowflakes. And I was very curious to see what Walter Kirn, who is one of these guys, had written in this issue. And he wrote a front of the book piece called “Weirdos Win Big” with the great dek, “Hey, Jocko, who’s the freak now? Normality is the new deformity.” I’m like, ugh, the ’90s. The copy in this magazine is really good.

The Fine Print: I hear a lot of it was Sam Sifton.

Leonard: Really, that’s funny.

Co-workers remembered the young Sifton mostly fondly. “Very elitist. He was so goofy that you were kind of charmed by it. But if you crossed the line with him, he would get — I think he’s chilled out from what I can tell,” said Clark. “Sifton was hardcore, but he came across like a real goofball. His hair was receding at the time, so he shaved it down. He was always red-faced and excited and happy to talk to people. People loved him.” Saffian remembered Sifton as a champion. “He was very encouraging,” said Saffian. “I wrote this book and it did well, and then I was basically back to fact checking. I remember he was like, ‘What are you doing? Go write another book.’ He was just very supportive and believed in people.”

The Fine Print: But there’s a phrase in here that was like Walter Kirn has never changed.

Leonard: 100%. He’s complaining that everybody has to have a trauma now to get attention. So he says everybody has to have their pain, blah, blah, blah. “And so Roseanne flaunts failed marriages. Fiona Apple chats up her rape. These days we all play the pathos card — even presidents, as Monica Lewinsky has testified. Gaining credibility through pain, however, requires legitimate trauma, and lately there just hasn’t been enough to go around. Luckily, a one-size-fits-all solution has been found. On the evidence of NBC’s new fall drama Freaks and Geeks, the last form of suffering left to otherwise successful Americans is to have been unpopular in high school.” This is a review of Freaks and Geeks basically. And then he goes through talking about how now the hero is the sensitive nerd, blah, blah, blah. And then I feel like in the clincher paragraph, he really defined his sensibility and lashes out at the snowflakes on behalf of the real, normal Christian Americans. And he says, “Still one crucial question remains: Now that feeling excluded is in and youthful inadequacy is a must, who will be the new pariahs? Attractive athletes? Eagle Scouts? There seems to be no way around it. There’s no one left. Freaks who can point to their own network TV show are by definition no longer freakish, while America’s churchgoing varsity quarterbacks are surely feeling increasingly like outsiders. With no one left willing to admit anything but a miserable adolescence, normality may be the new deformity.” And you get the sense that he’s already feeling victimized on behalf of America’s quarterbacks — I mean, it’s really amazing.

The Fine Print: County Highways is already there in the twinkle of his eye.

Leonard: Totally.

The Fine Print: I wonder if having contrarian writers leads to that sort of liability — they might go off the rails following their contrarian instincts?

Brown: Well, they might well do, but I’ve always liked contrarians and I always liked taking risks with writers and letting them have their voices, which is why Tom Stoppard wrote that piece. It was doing things that you haven’t really done before.

Much of the magazine’s front-of-book lives under the rubric The Conversation — tagline: “exploring news and investigating pleasure.”

The Fine Print: I wonder what you thought, generally of this conversation section because I had a bit of a hard time with it, I have to say, because I think it’s just so so so so overstuffed with such short pieces that by the time I got to the big features, at the end, my attention was kind of scattered.

Leonard: I have to admit, I’m sympathetic to an overstuffed front of the book. I like a lot going on. I like being able to open it at random and find myself reading something that apparently I missed. So I guess I was sort of into it, actually. I think among contemporary magazines, almost the only one that earns its print edition, when you don’t need a print edition anymore — apart from Lux, which, of course, everybody needs to read in print — is New York magazine, which has a tremendous front of the book. It’s very entertaining. But to your point, a lot of New York magazine’s front of the book is like the 1500-word piece, not interrupted by too much garbage, but with good photography. I think that is sort of the ideal format. And it’s true that the layout, it’s distracting to read because everything’s in tight columns. And then sometimes they’ll insert a box with a different article on a page that’s already divided into tight columns. It can be a bit much.

Part of that scattered sensibility might be a side effect of the staff having spent much of a year on this first issue.

Traister: I think because people didn’t know what it was going to be, there was so much indecision. A year to lead up to the launch of a magazine is just so much time. The ways that assignments were huge, and then were shrunken down to a caption. You know, 10,000-word feature! Nope, just kidding. It’s gonna be a caption. Nope, just kidding. It’s going to be a 4,000-word feature. Actually, we’re going to run it as a sidebar. That happened, in many instances.”

Sarah Saffian, the Talk reporter-researcher, remembered strategizing around Brown’s chaotic whirlwind.

Saffian: She would sometimes want to just blow up the magazine in the 11th hour. And so there was this strategy about pitching her something, that you didn’t want to pitch it to her too soon in the cycle, because she’d get sick of it and it wouldn’t see the light of day. So you would wait til the last minute and then it was the new shiny thing. Like no, we must do this and scrap all of that. I don’t know if she was as bad as the reputation but there was definitely some of that and we were all affected by it. Where we were like, I’ve been working on this piece for two weeks and now it’s killed. Okay. What’s next? You know, you have to trust there’s a method to the madness.

Traister: You probably will hear the story of the summer of ’99. It had been going for a year at that point, it was going to launch in September, and when John Kennedy [Jr.]’s plane went down, Tina ripped up the whole magazine. It happened over a weekend and there were a lot of people at Talk magazine who were very personally close to and associated with John Kennedy, Carolyn Bessette, and his family, some of whom were at the wedding that he was flying to. Her staff was experiencing grievous loss and pain. The thing I remember, and this is me maybe beginning to like, scratch my head about how journalism works, as it was happening, there was this push to get a story out. And it’s like, but there’s no magazine yet. We were still two months away and everything that had been slowly being put into place was ripped up. It was as if it were a daily or a weekly, the frenzy to remake the editorial map and well.

Brown: This was a really big explosion in the magazine, because there were several of them there who knew him well, or who had somehow had truck with George magazine, his magazine. And it was a big trauma. Of course, I’m afraid, being the editor that I am, and I’m being honest here, I thought, oh, my god, is this going to change the zeitgeist completely? We’re about to come out with the Talk magazine with Hillary on the cover. We’re going to come out into this massive John F. Kennedy moment and we’re not going to have anything. I was very, very concerned about it. One of my contacts said, “Oh, you should call Peter Beard. He has these childhood pictures of John F. Kennedy Jr.” And one of them was of him flying a helicopter. And I tore up the magazine and we put in the six pages. And so I had my John F. Kennedy cover line. And we were lucky because it was just two weeks, or 10 days after it happened. And you know what I’ve learned as an editor? The absolute gangbang mourning cycle that happens in America when a celebrity death happens, everybody goes nuts, whether it’s Michael Jackson, or whether it’s John F. Kennedy, Jr. Whoever it is, there’s a kind of media horrendous piling on, and it explodes. And people are obsessed, and it goes on, and then, all of a sudden, it ends. People don’t want to read another story about the celebrity in question. So actually, we came out two weeks afterwards. And that whole thing had just obsessed the media and in the horrible fickle way of American concentration span it had sort of moved on. And actually, it was really great to have these pictures, because they were elegiac, because it was an incredibly sad and terrible story and to be able to celebrate it in an elegiac way was just the mood that you wanted to be in actually. So it really worked very well.

Among the other challenges confronting the staff was Brown’s emphasis on stories told in the first person from the perspective of participants in dramatic events. A prime example in the September ’99 issue is “The Last Safari,” by Mark Ross, an American safari guide who survived being taken hostage by Hutu rebels in Uganda.

Brown: That piece, I think it was really written by Jonathan Mahler. So the idea was, get the guy to give us the story, we’ll team you with a writer-editor and we’ll make this narrative into something we can publish. This concept of creating narratives, from unlikely places, where we’d found those people in the news was a central pole of the idea for Talk magazine. We really tried to get these voices that were not writers telling their stories, and we were very successful at it. But it’s quite an onerous thing to do if you are an editor to extract that material from people.

Leonard: It’s interesting to look at some of the more substantial reporting pieces because they very much speak to the time and they turned out to be sort of still relevant. There’s a piece on Juarez, Mexico and the many, many young women who were traveling there to work in factories, and some of them also trying to go to school. And there was a slow-building murder of these women. There were just regular murders and bodies would turn up in crazy places, and it’s pretty horrifying. And he’s correlating this with NAFTA ending tariffs and the peso being devalued and having this city in which there was this brutal, very feminized factory work. And of course, today there is a massive movement in Mexico and actually throughout Latin America against femicide. I was finding it actually helpful to look back at this reporting from ’99 and see how people were explaining its origins at that time. I think the Juarez piece, for example, is not something that really defines the sensibility of this magazine exactly. It’s not given the same space as the political profiles, for example. But it is an important part of the work that I think is really strong in this magazine. It gives it some weight, but the bulk of what’s here is not exactly that sort of thing.

The Fine Print: It’s interesting to compare that Juarez piece with the trailer park piece. Like the Juarez piece, I think, actually engages with people struggling in a real way, versus the trailer park piece felt very voyeuristic to me.

Did Clark have a sense of the reader Brown was imagining? “It was her people, she was writing for her people,” she said. “She was taking her life and trying to expose us all to it. Certainly I was never exposed to this level of academia, intellectualism, art. This is a woman who was going to take you inside and show you everything. To me her magazine — if you wanted to be in the elitist crowd, if you wanted to go to a party out in the Hamptons, you read this magazine, you’re set. She literally made a little compact how-to manual of how to be with the haves.”

Leonard: Totally. I mean, you have a very clear sense of who this magazine is for. This magazine is for people with expendable income, probably in cities, and you can see it in the ads. One of the things that was kind of fun about this, honestly, was looking at all of these ads that I looked at throughout my childhood. All the supermodels are in these ads. It’s like a young Giselle in a Ralph Lauren ad, or like Cindy Crawford advertising a sweater. I was like, it’s really the ads of my childhood, but it’s all Gucci. This is an ad for people spending money. There’s an entire article in the front of the book about the return of fur in high fashion and the guy who manufactured that demand. And it’s kind of a great industry story, but primarily relevant to people who wear fur.

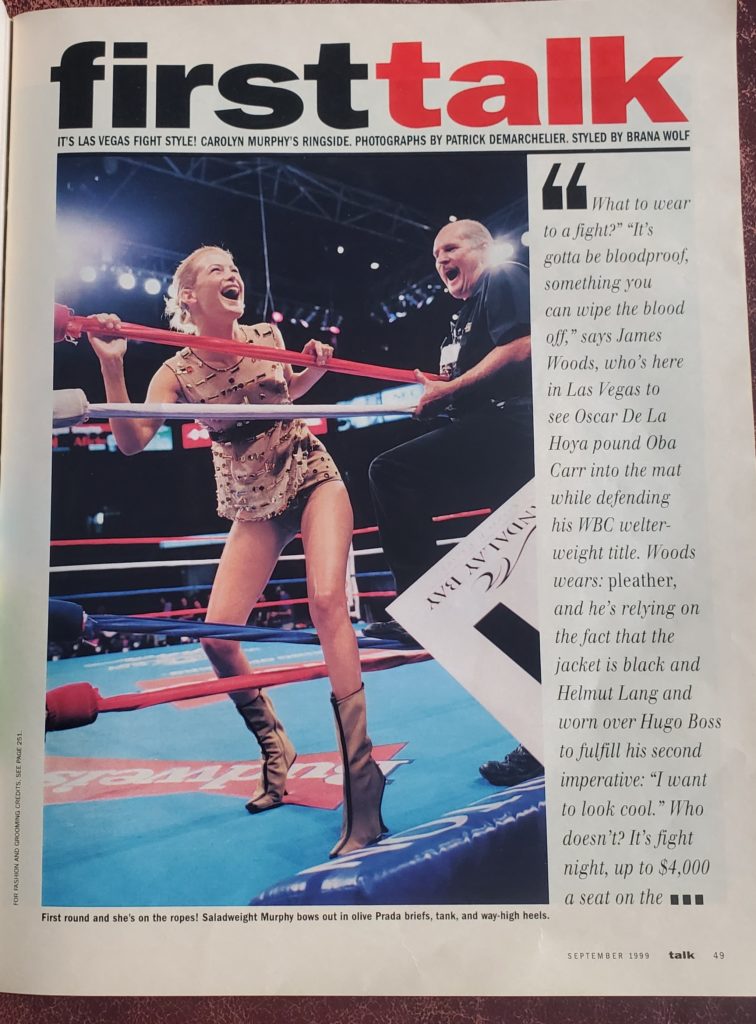

“Saladweight Murphy bows out”

The Fine Print: Some of the captions though, do feel like they step over a line. They’re the bits where I’m reminded that this is a Weinstein-funded magazine — for instance, the Angelina Jolie shoot and the Gwyneth Paltrow shoot.

Leonard: Oh, yeah. Yep. Yep.

The Fine Print: Those are weirdly placed in the magazine too.

Leonard: Yeah, they’re kind of like in the feature well, but they’re just hot pictures with like five paragraphs.

The Fine Print: Right. And the Gwyneth Paltrow one for instance, especially the centerfold one, she looks so, so uncomfortable.

Leonard: It’s like the worst Gwyneth Paltrow pictures and it’s not her sensibility at all.

The Fine Print: There’s this line at the end of the caption that sort of speaks to it not being her sensibility — this came out right after Shakespeare in Love — “Next time Paltrow plays the muse of a famous writer, here’s hoping it’s the Marquis de Sade.”

Dawson: Oh my God! Holy moly.

Clark remembers Weinstein’s priority being getting Paltrow on the cover.

Clark: It was definitely Harvey and like she didn’t want to do that. I mean, to be clear, that was not something she wanted to do. And he was her godfather, and he definitely stepped in. And that was a tumultuous conversation. She really, from what I understood was pushed into that, specifically the a la Barbarella style. As much as I think we pushed a lot of the envelope forward on many things — certainly in that issue for Hillary, that was not a typical stance people took on Hillary at that time, and I think it was wonderful that we took that sort of enlightened, glowing, albeit rare take on her — I think we set ourselves back with the Gwyneth thing. But it wasn’t very public at the time. Nobody really understood that he controlled her to that level.

Traister: We’re having this conversation, five or six years after a recent explosion around gender, power abuse, sexualized power abuse, sexism itself. The reason that these things happen in these culture-shaking explosions is because they are sublimated, accepted and worked through as part of just how culture and power and business works for years. I wish I could think of all the reference points. Some of the celebrity profiles that have run even well beyond the ’90s, in the 2000s, that were just so vile in their sexist objectification of the women that they covered, or openly homophobic. That stuff was just mainstream for such a long time. We were raised with that. I mean, I remember conversations about feminism that took place at that magazine that were especially coming from the top down pretty anti-feminist. Like “feminism isn’t cool,” directly. Which, I hasten to say, it was not. Not cool. It wasn’t wrong. The post-second-wave backlash that lasted through the ’80s and the ’90s — and certainly there was already a zine culture and a riot grrrl culture in the ’90s that existed on the margins — but it had not extended into mainstream glossy journalism, which was still very much supporting all the anti-feminist backlash impulses of the Reagan era through the ’90s.

Brown: The time was the time. At that time, feminism was actually uncool, although much of what I published was by very strong women about very strong women. I think every moment in time, that’s the ephemera of magazines — they’re a mirror of their times. It’s why magazines are interesting to look back on, it’s like this was the zeitgeist of that moment.

Leonard: A funny thing that I think is smart about Tina Brown, even though I think we can agree these pictures are not persuasive — she’s big on not just the intellectual but the visual scoop. So like, what’s a picture that people are going to talk about? And it reminds me that at the time, when she edited Vanity Fair, her most famous visual scoop was getting that picture of the Reagans dancing together and kissing. This was unusually intimate for a president. It’s kind of hard to imagine it making the news now, but it did then. And that was a time when the result was that she went on the morning talk shows to explain that picture to everybody. It was news in itself, the magazine got covered by television. You kind of got that sense here, that they’re trying to do something that’s visually provocative enough with a celebrity that they have a visual scoop. How did that happen? Like has anyone ever seen Gwyneth Paltrow look like that? You know, like, it’s something to talk about. And it has that sensibility more than like, it’s not this is a beautiful photograph. It’s, can we make a little bit of news with this photograph?

Brown: The idea was to make people experiment, which is why we have that wildly un-PC, if you like in those days’ language, shoot with Gwyneth Paltrow in S&M gear, which you probably wouldn’t do today either. So it was all about how transgressive can we be visually? And we had this thing which Gabé started called Dream Roles. The idea was, you’d ask a movie star, is there a role you wanted to play? And then we would shoot them in the role, essentially.