A Betting Guide to New York Times Succession

Speculating about who will be picked as the next executive editor is the media's favorite pastime

There is no greater spectator sport in New York media than speculating about who will be the next executive editor of The New York Times. Other people may enjoy keeping up with politics or sports, but in certain circles, if the subject drifts to the succession at the country’s leading news organization, you’re bound to fall down a rabbit hole of stray data points, supposed insider tips, and elaborate theories. In truth, no one has any real information — not even the “Times insiders” who get quoted in pieces (like this one) that purport to shed light on the question. That’s because the process of selecting an executive editor is opaque and closely guarded: the decision is technically in the hands of just one person, A.G. Sulzberger, the dynastic heir to the throne of New York Times publisher. It’s sort of like the selection of a Pope, but without the democratizing influence of a College of Cardinals. But that’s also why it’s such an irresistible discussion topic for media types: Everyone has an opinion and unconstrained by reportable facts as they are, they all have an equal chance of being true. So, anyone can play.

Dean Baquet, the office’s current occupant, turned 65 — the traditional, if malleable, Times retirement age — on September 21, which means this particular succession speculative cycle is nearing its apogee. But while the blathering heads on sports radio and cable TV come armed with statistics and narratives about why the Knicks don’t (or do) have a chance this season, there has been no equivalent for New York media’s favorite pastime. So that’s why The Fine Print has decided to give the matter the thorough and careful attention it deserves.

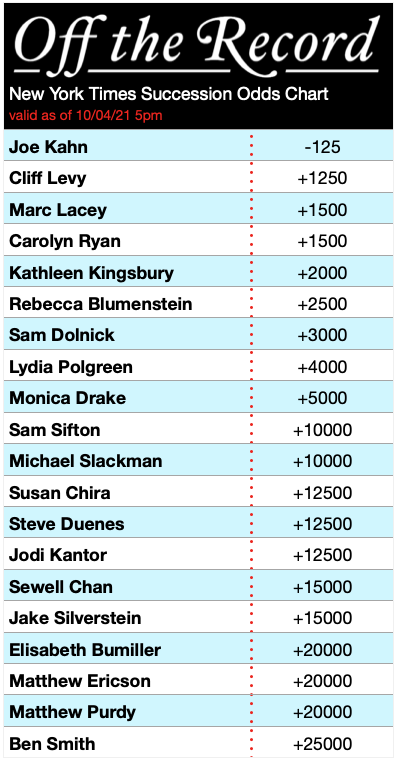

Armed with a plenitude of context and an inexhaustible numerical incomprehension, we turned to The Fine Print’s stable of quants and their exascale server farm. “If you feed it facts,” they said, “it’ll give you odds.” Their algorithm gave us American odds, which are slightly counterintuitive: lower numbers are better. If the odds are negative, that means someone has a better than 50 percent predicted chance. That’s where Joe Kahn, at -125, stands in our lineup. To win $100 off a bet on Kahn, you’d have to put up $125. For all the contenders with plus-odds, that number is how much you win if you bet $100 and the candidate becomes executive editor. A $100 bet on deep long shot Ben Smith would net you a cool $25,000.

There would have been no point in putting down bets in 1964 when then-newly appointed publisher Arthur Ochs “Punch” Sulzberger Sr. created the executive editor role to unite editorial management of the daily Times with the Sunday edition. Practically, Sulzberger had only one option: Turner Catledge started at the paper in 1929 and had been its managing editor, then the top editorial title, for more than a dozen years. In some ways, the executive editorship was more a form of title inflation than a substantive promotion. But for most of Catledge’s successors, and the competitors they beat out, the role became the focus of much Machiavellian scheming.

The eight executive editors that followed have employed different strategies to get to the top. Some, like James “Scotty” Reston or Howell Raines, have cultivated unusually close personal relationships with the Sulzberger-in-charge. Reston’s short spell at the top, from 1968 to 1969, was so underwhelming that Punch Sulzberger retired the executive editor title until 1977. Raines won the post in 2001 after an epic internal struggle and dramatically revamped the paper and won a slew of Pulitzer Prizes, but left the job after only two years in the wake of the Jayson Blair scandal. Others, like Max Frankel and Joseph Lelyveld, distinguished themselves as foreign correspondents, moving up the masthead primarily through the close relationships they formed with the executive editor that preceded them.

The two most recent executive editors, Baquet and Jill Abramson, were similarly their immediate predecessors’ managing editors. “Reporters in the newsroom talked about ‘Bill and Jill,’ as if they were talking about ‘Mom and Dad,’” Abramson wrote in her book Merchants of Truth of how closely she worked with her predecessor Bill Keller. She described the kind of careful career calculations contenders do when considering new roles within The Times. “An additional motive for my going digital,” Abramson wrote of a period when she worked with the Times’ nascent web team, “was to prepare in the event I succeeded Keller.” But it was not enough: in the wake of an Innovation Report that A.G. Sulzberger led, casting doubt on her digital chops, Abramson was dismissed in 2014, just shy of three years in the job and replaced with Baquet.

Now a new generation of hopefuls has gathered at the upper echelons of the Times. Until last summer, it appeared that James Bennet, the former editor-in-chief of The Atlantic who had joined as opinion page editor in 2016, was a shoo-in for the job in a race that pitted him against managing editor Joe Kahn and deputy managing editor Cliff Levy, and that a transition could come soon after the 2020 election. (The Times often likes to make big management moves following a presidential election.) But Bennet flamed out last June when he resigned from the Times following the controversy around an op-ed by Senator Tom Cotton urging the government to send in troops against Black Lives Matter protesters. As a headline for a Vanity Fair piece by Joe Pompeo blared out, the scandal “scrambled succession at The New York Times.”

While it felt as if Bennet’s exit had hit a reset button on the succession race, Baquet appeared to be proceeding with plans beyond The Times. In January this year, it emerged that he had purchased a home in L.A. And while insiders say Baquet is as engaged with running the paper as ever, a company spokesperson broke out the R-word when explaining the transaction: “He’s rented an apartment there for a few years, his son lives there, and it’s likely where he’ll settle when he retires.” Meanwhile, a rumor began making the rounds that Sulzberger had asked Baquet to delay retirement to allow additional time for a search for his replacement.

After our data scientists returned with the results, we felt ready to take a look at the odds. The Fine Print’s NYT Succession Odds rank each potential candidate individually, but on closer analysis, several distinct groupings emerge.

The Front Runner

While there is an air of inevitability about Joe Kahn (-125), there is not much detectable fervor. “I don’t hear Joe Kahn with any certainty,” said one Times insider, who admitted they hope an alternative emerges. As a managing editor is supposed to, Kahn has a commanding presence at the paper — his voice is the most frequently heard at the daily news meetings — but within the paper, he is known more for the first part of his title than the latter. So if not a swell of support from the newsroom, what explains the consensus?

One of the most intriguing theories points back to Baquet as the most motivated person to get the transition over with. Now that he’s turned 65 — the most commonly touted version of the “mandatory” retirement rule is that it means anytime before a person’s 66th birthday — he is at risk of having his retirement tainted by any new scandal that happens to come along in the next year (or whenever he retires). So, the theory goes, it would be in his interest for everyone to get used to the idea of Kahn now so as to get the thing done before another periodic outrage eruption engulfs The Times. It’s just a theory, and one, for what it’s worth, others at The Times disputed.

The most frequently aired reason against Kahn’s elevation is his involvement in a scandal that seems to have passed without leaving much of a mark. Last December, The Times retracted much of its award-winning Caliphate podcast series about Islamic extremism after a supposed terrorist who was a main character in the series was arrested in Canada as a hoaxer. When doubts about the source were raised internally during production, Kahn, a former international editor, was reportedly one of the high-level editors (along with Baquet) who backed star correspondent Rukmini Callimachi’s push to carry forward. The editor’s note announcing the retraction cited the absence of the “regular participation of an editor experienced in the subject matter” as a key institutional failing in the episode. But while Callimachi has been reassigned to the national desk and the series’s producer and co-host, Andy Mills, exited The Times, Kahn never became a central player in the controversy.

After about an hour’s worth of theorizing about other contenders, that hesitant Times insider was resigned. “I do think it’s going to be Joe Kahn.”

The Next Tier

In the wake of Bennet’s departure, amid widespread global protests against racism, there seemed to be a more concerted effort to advance a more representative candidate pool. Two names to emerge were Marc Lacey (+1500), then the national editor and one of the highest-ranking Black editors at the paper, and Carolyn Ryan (+1500), an assistant managing editor and one of the highest-ranking openly LGBTQ editors, who had come up as political editor. After overseeing the 2016 election, Ryan was given the remit of managing recruitment and spearheading the paper’s diversity and inclusion initiative. Last year, both saw their profiles in the succession discussion rise. Shortly before the 2020 election, Ryan was promoted to deputy managing editor, in recognition, the release read, that her role is “at the center of our leadership agenda.” A couple of months later, Lacey was promoted to assistant managing editor in charge of the burgeoning Live operation, a newsroom division that produces the live briefings (a giant web traffic driver) on massive stories like the pandemic, protests, and the election and its aftermath. Recently, though, talk about Lacey and Ryan seems to have cooled a bit. Lacey is no longer the presence he once was at the news meeting (that role has gone to Jia Lynn Yang, who succeeded him as national editor in February). And Ryan’s profile, given her close identification with politics, seems to follow the ups and downs of the quadrennial electoral cycle.

While they’re both still solidly in the second tier, Cliff Levy (+1250), currently a deputy managing editor, is most often cited as the not-Kahn contender. Having joined The Times in 1990, Levy has the longest tenure at the paper of any of the contenders. (Kahn joined eight years later.) Known internally for his ambitions, in recent years he’s made a reputation for successfully tamping down crises in the newsroom’s various trouble spots. In July, he was tapped to head the Standards operation, which has been tasked by Sulzberger, in a sort of sequel to his Innovation Report, with “deepening our audience’s trust in our mission and in the credibility of our journalism.” Earlier this year, in the aftermath of the Caliphate retraction, Levy was brought in to oversee the audio division. Before that, in 2018, he was named metro editor with the mandate of turning the section — which though it had one of the largest staffs in the newsroom, was becoming less relevant to The Times’s national subscription strategy — into “a laboratory for his ideas and abundant creativity.” It was technically a step down from his previous title of deputy managing editor for digital platforms — itself a high profile role, working on the kinds of subscription apps that are now touted in quarterly earnings reports — but as The Times own coverage of the move put it, “This will be Mr. Levy’s first time running one of the paper’s news desks, a role commonly seen as a prerequisite for those who might ascend to the top newsroom position, executive editor.”

The Dark Horses

Two high-ranking women at The Times don’t get as much attention in the succession sweepstakes, but they share one thing on the org chart that makes them contenders: they each report directly to publisher A.G. Sulzberger. They’re also both relatively recent arrivals to The Times, which is a notoriously difficult place for outsiders, no matter how accomplished their prior careers are.

Rebecca Blumenstein (+2500) joined as a deputy managing editor in 2017 after a 21-year career at The Wall Street Journal, which is where she met Kahn, who was credited with recruiting her to The Times. At The Journal, Blumenstein was seen as a potential successor to editor-in-chief Gerard Baker. (Matt Murray eventually got the job after Blumenstein left for The Times.) When she arrived, in the wake of the departures of women who had been tabbed as likely future female executive editors, Blumenstein was touted in The Times’s coverage as “one of the highest-ranking women in The Times’s newsroom.” But that story included some bristling: “Ms. Blumenstein’s appointment will quite likely be seen as a positive step, though it is notable that The Times named an outsider rather than promoting a woman from within.” After holding several remits in the newsroom, initially to bolster business coverage (but not edit it, that’s business editor Ellen Pollock’s job) and overseeing the website and Live coverage for much of 2020 before Lacey’s promotion, in February she was named to the newly created role of “deputy editor, publisher’s office,” reporting directly to Sulzberger. A Times insider described it as a savvy move, allowing her to keep one foot in the newsroom (Blumenstein retained her masthead title) while also gaining the publisher’s ear.

Kathleen Kingsbury (+2000) also joined The Times in 2017 as deputy editorial page editor, recruited by Bennet from The Boston Globe, where she had been managing editor for digital and won a Pulitzer. After his exit, she served as interim opinion editor for the remainder of the 2020 election cycle before being named as the permanent replacement this past January. Reporting directly to the publisher, the opinion page head has long been seen as a stepping stone to the executive editor role. A Times source said Kingsbury has seemed to be amplifying Bennet’s ambitions for the opinion section as a sort of parallel operation, expanding beyond editorials and columns to its own array of digital offerings, including video and audio. One recent indication of her possible succession aspiration is the public role she’s taken in the initiative to expand email newsletter offerings as subscriber-only products. In a company announcement in August, Kingsbury was the only editor quoted. Adam Pasick, the editorial director of newsletters who had been hired in 2019 after helping to create Quartz’s popular Obsession newsletter, was left out entirely — though, in fairness, most of the newsletter writers are opinion staffers. Given the traditional firewall between news and opinion, there are not many opportunities for the opinion editor to get involved in big company-wide projects. One Times insider saw Kingsbury’s involvement in the newsletter project as her way of putting her name in the mix for future management roles. “She’s basically auditioning,” the source said.

Future Prospects

Now we reach the tier of names that get mentioned in succession discussions, not so much because they have much (maybe any?) shot of succeeding Baquet, but because they are seen as potential executive editors down the line. Mostly in their 40s or younger, these contenders would overturn the precedent of naming people in their late 50s or older. But then again, they are all closer in age to the current publisher, who is just 41 years old.

Sam Dolnick (+3000) is a member of the Sulzberger clan (his mother Lynn Golden Dolnick is a cousin of Arthur Ochs Sulzberger Jr., father of the current publisher) and so will always be on the list of potential Times executive editors. Before A.G. was named publisher, there was succession speculation about him, Dolnick, and David Perpich (son of the elder Sulzberger’s half-sister, Cathy Jean Sulzberger). When A.G. won his current role, a story began making the rounds, quite possibly apocryphal, that the extended clan had a cut a deal to ensure each of these members of the family would have a place of power at The Times: A.G. would be publisher and chairman, Perpich (who is currently head of Standalone Products, including Cooking, Crosswords, Parenting, and Wirecutter) would eventually become company CEO, and Dolnick would be executive editor. Whether there’s any truth to that or not, Dolnick, currently an assistant managing editor, has been steadily rising up the ranks on a similar trajectory to other Sulzbergers who eventually took leadership positions in the family business. He joined the newsroom originally as a metro reporter, became a feature writer (a magazine piece he wrote on an elderly courier for the Sinaloa cartel was adapted into the Clint Eastwood movie The Mule), then worked on the sports desk as an editor, and is now heading up The Times’s efforts in experimental post-text media like virtual reality and, more recently, its podcasts and TV shows for FX and Hulu.

Others lack family ties but are nonetheless regarded as the rising stars in Times management. Monica Drake (+5000) has been focusing on digital special projects since she was named an assistant managing editor in 2017, the first Black woman appointed to The Times masthead. At 55, Sam Sifton (+10000) is on the older side of this cohort but has been steadily rising up the org chart since joining The Times in 2002 as deputy dining editor before becoming a high-profile restaurant critic, founding editor of the Cooking app, and, now, an assistant managing editor in charge of culture and lifestyle. Another name that gets thrown into the mix is Jake Silverstein (+15000), who was named editor of The New York Times Magazine in 2014 after editing Texas Monthly. Unlike previous magazine editors who primarily lorded over their fiefdom, Silverstein has been a frequent presence in bigger newsroom initiatives, including Dolnick’s VR push and the 1619 Project. But some Times staff still voice the age-old critique that the magazine is too insular — or, simply, that its editors are too stingy about assigning magazine pieces to newsroom writers — a historical grievance which could hinder any potential executive editor ambitions.

And then there are two longer shot wildcards: Jodi Kantor (+12500) is best known outside The Times as a big-shot investigative reporter. Along with Meghan Twohey, she shared a Pulitzer for The Times’s pioneering #MeToo coverage. But when she first joined The Times in 2003, she was a 28-year-old wunderkind given the editorship of the Arts & Leisure section, under the tutelage of columnist Frank Rich, who was made a kind of culture czar by then-executive editor Howell Raines. There are some at The Times who suspect Kantor still harbors ambitions of returning to management. Or at least Ben Smith (+25000) has. In 2019, a couple of months before he joined The Times as media columnist, while he was still editor-in-chief of BuzzFeed News, he included Kantor in a succession speculation piece he wrote. As for Smith, the longest shot of the bunch, he’s on this list primarily because he’s been telling people that he thinks he could be executive editor one day. While building the BuzzFeed newsroom took management chops, it’s pretty unfathomable that The Times would elevate a columnist straight to the top job. Then again, Smith is coming off a week where he ethered a whole company with a single column. He’s riding high, so who knows?

The Prodigal Daughters and Sons

One of the consistent problems at The Times is that its sheer size and accumulation of highly intelligent and ardently ambitious people creates a logjam towards the top of its org chart. For young stars, particularly ones with profiles outside The Times, it can create a dilemma: stick around and slowly work through a series of middle management jobs or strike out and claim a leadership position elsewhere right now? While many have departed for bigger jobs than The Times could offer, there isn’t a long history of returnees. Except for a notable one: Dean Baquet was national editor at The Times in 2000 when he enlisted as managing editor of the Los Angeles Times and took over at the paper in 2005. The following year he exited in protest of newsroom budget cuts and landed back at The New York Times as the Washington D.C. bureau chief (technically a lower rank than the one he had left), restarting his ascent to the executive editor spot.

Several other recent departees are sometimes mentioned as potentially following a similar path: Lydia Polgreen (+4000), who was an associate managing editor when she was named editor-in-chief of HuffPost in 2016 and is now the managing director of Gimlet Media at Spotify; Susan Chira (+12500), a longtime and well-liked Times editor who held multiple management positions before succeeding Keller as the editor-in-chief of The Marshall Project in 2019; and Sewell Chan (+15000), once a young Times star who left in 2018 to take the deputy managing editor role at the Los Angeles Times (now under new ownership since Baquet’s days) and is soon to take over as The Texas Tribune editor-in-chief. It’s doubtful any would come back straight to the executive editor post, but they are still names to watch for succession obsessives.

The Rest of the Masthead

Anyone on The Times masthead is, by definition, in the executive editor candidate pool. But whether it’s because they’re satisfied with their current briefs or they simply don’t have a predilection for pushing their names into circulation, this group is viewed as largely non-combatants in the succession sweepstakes: deputy managing editors Steve Duenes (+12500), the head of The Times graphics operation, whose star has risen as the paper transforms to digital, and Matt Purdy (+20000), known for overseeing investigation efforts; and assistant managing editors Elisabeth Bumiller (+20000), who also leads the D.C. bureau, Matthew Ericson (+20000), another former graphics editor who now focuses on digital publishing tools, and Michael Slackman (+10000), a foreign correspondent veteran who now oversees international coverage, which is a traditional path to the executive editor perch.

The next task we’ve set for our quants is arranging The Fine Print’s NYT succession betting pool. We’ll report back on how our readers can get in on the game soon.