Con Men, Set Design, Extreme Novelty, and Marxist Poetry

This week, curl up with works by Sean Williams, Noah Gallagher Shannon, Sindhu Gnanasambandan, Abbey Lustgarten, and Kim Hendrickson

Sean Williams in Rolling Stone: “He didn’t feel like just any source; it seemed like we were on the same side. Partners, even. And that was a dire mistake.”

Sean Williams in Rolling Stone: “He didn’t feel like just any source; it seemed like we were on the same side. Partners, even. And that was a dire mistake.”

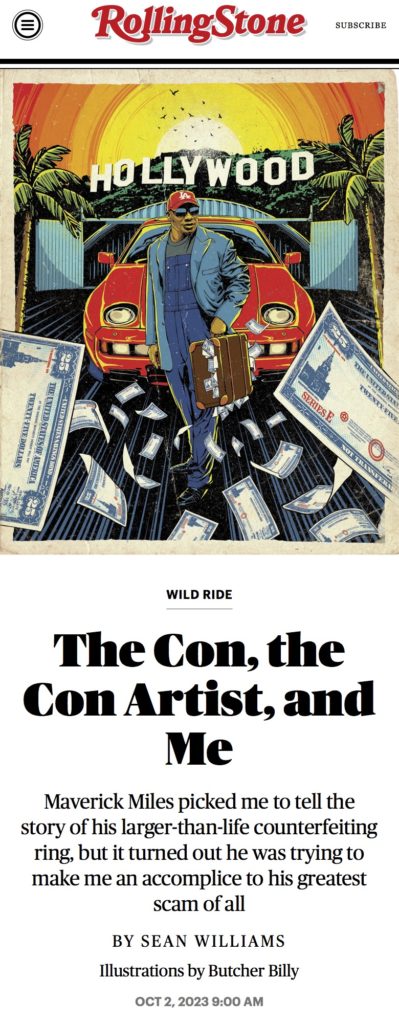

Rolling Stone’s journalistic reputation took a devastating hit in 2014 when a story they had published about a rape at the University of Virginia was revealed as a fabrication. So it’s notable that the heroic turn in this Rolling Stone caper about how reporter Sean Williams got conned by Derek Kelly, the con artist he was writing about, is credited to fact-checker Brenna Ehrlich. By then, Williams had palled around Atlanta with the con man, who was going by the improbable name “Maverick Miles Nehemiah,” let him pay for their meals, and shared a rough draft with his subject. Kelly had given him the name of a woman who would be helpful to talk with. “I was going very, very deep down a rabbit hole of contacting everyone with that name in the Midwest, and no one existed. So I was starting to get extremely suspicious of him at that point,” Williams told The Fine Print. In February, he messaged his editor Maria Fontoura to say, “This isn’t adding up at all.” Fontoura assigned Ehrlich to help dig into Kelly’s background, and on February 28, the researcher found a forum post listing the man’s aliases. “That caused the whole thing to spill out,” Williams said.

“The truth of it was extremely odd and far weirder than the original story ever was,” Williams said. “The original story hadn’t really had that handbrake turn moment in the plot. It was a smooth ride, which doesn’t always work. But actually, when you find out the truth of the matter and it explodes into this whole world — four decades of cons and scams and whatnot — from the very first moment that we were both on the phone saying, ‘Oh, my God,’ the editor was immediately like, ‘Right, this is actually a way better story.’ So there was never any talk of killing it.”

Kelly had astroturfed a false story about how he’d committed an epic $20 million con in order to get written up in articles like this one and perhaps end up as the central character in a film. “He had started seeding this character years and years ago with various contacts. He’d sent letters to people about this Maverick Miles character and this counterfeiting scam. And then, a few years later, he starts putting out self-published articles in magazines,” Williams said. “It really was the pinnacle of his scamming career to try to get this in Rolling Stone, and then to get it into a Hollywood deal, which he honestly came frightfully close to getting.”

Earlier this year, while they were still working on restructuring the story around the checker’s revelation and uncovering the extent of Kelly’s scam, Fontoura left Rolling Stone to become the editor-in-chief of Us Weekly. “When Derek found out that I was reporting the real story and that Maria had subsequently left the magazine, he began telling people that Maria had been fired because of my malfeasance as a journalist,” Williams said. “That’s part of his official story, which is quite funny.” The editor who carried the story across the finish line was Sean Woods, who had been the main editor on the disgraced UVA story.

“The psychology of con artistry is that no one thinks they’re gonna get conned. And being someone who is in regular life profoundly cynical and trying to analyze things on a reporterly level, it was shocking to me that I was able to be pulled into his orbit and for so long believed his bullshit,” Williams said. “I think he did see vulnerabilities. On a couple of levels, really. He had seen that professionally I was really, really interested in the story and I was really eager to report it, which I think was a mistake and I let that kind of professionalism slip at the start in being very, very keen on telling what was clearly a very filmic story.”

Magazine publishers have gotten ever more voracious in swallowing IP rights in recent years, but Williams was able to negotiate “a decent percentage” for himself. “Also, it was very clear that my life was somewhat in flux. I was expecting a child. I’d moved countries twice in a few months. Everything was sort of haywire. And I had a couple of other stories that I was working on in the background, at that very time, that were huge pieces. So I was just pulled in about a thousand different directions. He was able to slip under my radar slightly for a while. But also, my own gullibility worked to my advantage, because he would never have gotten that deep with me unless I’d have let him go that far with his con,” he said. “I wouldn’t have gotten Rolling Stone so invested in publishing the story had I expressed so many doubts about it to begin with. I think because I was so evangelical about the piece, that helped it get commissioned. So, conversely, him picking me out as a mark was the reason that he got screwed in the end.”

Williams wouldn’t exactly call writing this piece fun. “He was able to get me to hand over a bit of my writing, which is quite embarrassing to see that you can be played like that. It’s pretty embarrassing to look back and have to commit that to print, because it’s not the greatest moment of my career,” he said. He’ll be doing things differently on future stories, starting with taking more attentive notes during in-person interviews. “I’ve learned a lot about how I deal with subjects in person,” he said. “My instinct, and I don’t think it’s incorrect, is just to let someone speak a lot more fluidly and eke out the heavier scrutiny over time. I don’t think I’m going to change that with subjects, but I think I’ll be a lot more methodical about any inconsistencies that I sense on the spot.”

➽ Bonus: At Literary Hub, Adam Dalva profiles another subject who doesn’t really want to be seen, novelist Benjamín Labatut.

Noah Gallagher Shannon in The New York Times Magazine: “He has sought over a half century to scour away the visual clichés that mar films, seeking beneath them the vivid woodgrain and forgotten colors of the past.”

Noah Gallagher Shannon in The New York Times Magazine: “He has sought over a half century to scour away the visual clichés that mar films, seeking beneath them the vivid woodgrain and forgotten colors of the past.”

Jack Fisk, the production designer behind Killers of the Flower Moon, There Will Be Blood, The Revenant, Phantom of the Paradise, Mulholland Drive, and most of Terrence Malick’s films, was a reluctant profile subject. “We talked for maybe a year or two before he agreed to do this,” Noah Gallagher Shannon told The Fine Print. “I initially reached out in 2021, when he was working on the production [of Killers of the Flower Moon], and he was basically like, ‘Yeah, I’m making the movie, I can’t do something like this.’ He just seemed a little reticent, I think, because his job has been to be in the background.” Shannon first got interested in Fisk precisely because of how much of his work has been in the background of so many cinematic touchstones. “He was one of the most recognizable artists in the world, though nobody knew his name,” he said. “And then, Jack, of course, is such a gift of a subject because of his background, having grown up with David Lynch and being married to Sissy Spacek, and then having this hint of mystique around him as a result of being Malik’s closest collaborator for so many decades.

It was Shannon’s interest in bringing production design to the fore that got Fisk to sign on. “He got more excited about helping more people understand what production designers do,” Shannon said. “I think a big part of his career has been trying to spread the art form, and he seems like a great mentor to a lot of young production designers, so that was also the mode in which he was thinking about the profile.” Once Fisk was on board, he was fully on board. “Jack was just so fun to talk to,” Shannon said. “This would often happen, where I would call him or text him about some small detail, and then we would jump on the phone, and we would talk for four hours.”

Fisk became interested in how Shannon was going about his work in return. “At first, I tried a little bit more of a meta approach to the profile, just because he had been so interested in the idea of a profile. Like, ‘How do you start? What’s the first image that you give the reader?’ He’s almost thinking like a production designer for his own profile,” Shannon said. “Not in the vain way that a profile subject might be trying to control what’s being said about them, but in this way that seemed almost like Jack was such a natural collaborator, and had done it for so long, that he was always thinking about my creative task, and wanting to help me or talk things through. Like, ‘Yeah, how might you use this?’ Or, like, ‘Am I making sense at all? Is this helpful for you?’ Almost in a meta way, wanting to help me put together the story or help me make sense of what he was doing.”

Shannon toyed with that meta-framework for a while, but he ultimately went in a different direction. But there are still traces of it in the finished piece. The moments of satisfaction for Fisk that Shannon routinely describes are moments of factual confirmation that feel almost journalistic. Fisk imagines a barbershop in a pool hall in his latest film; when he later checks the Osage County fire maps, he discovers that two out of three pool halls in the real setting had barbershops. Visiting Guadalcanal for Mallick’s World War II film The Thin Red Line, he found unexploded grenades of a design he’d found in his research and already intended to use. “He often said his work was kind of like being a detective — he was always trying to find something that no one else had found before, and using it so that the history in the film would come back alive, and would have a human touch to it,” Shannon said. “So we did talk about how certain aspects of our work were the same.”

Though Shannon usually structures his stories carefully before sitting down to write, this time, he decided to just give himself permission to write about whichever theme or approach he was interested in at a given moment. There were so many aspects of Fisk’s work that he was fascinated by that he worried about giving any of them short shrift. “With someone like Jack, my bigger worry is trying to do justice to the sheer range and impact of their career and trying to distill that all down into 7,000 words,” he said. “There are whole decades of his career I just didn’t write that much about.” In the piece, he writes how the production designer goes around removing furniture to strengthen the impression he’s giving. “I’ve looked at Edward Hopper for a lot,” Fisk tells him, “because in putting together paintings, realist painters kind of simplify the world. They pick out what’s important and what they want to make strong.” Did that give him any solace when he worried about not covering everything? “No.”

Near the end of the profile, Fisk struggles to understand Mollie Burkhart, one of the main characters in Killers of the Flower Moon. He had to find a home that spoke to the character, an Osage woman made newly rich by oil and her family and community members start dying suspicious violent deaths. “Fisk was wary of casting Burkhart’s story in generalizations,” Shannon writes. “If you don’t know where they lived,” the production designer asks, “how do you know what kind of people they were?”

The piece winds up with Fisk’s capacious imagination shifting from Burkhart’s home to the dwelling of the raccoon in Guardians of the Galaxy. That’s the biggest difference from the draft Shannon submitted to his editor Willy Staley. “With how big Jack’s career has been, I had an instinct to want to summarize or editorialize at the end of a piece. Willy had a really sharp eye in landing on Jack thinking about the nature of what he’s doing and making a good-natured joke about the incursion of this other kind of art form,” Shannon said. “I had two more paragraphs after that, and the move was just to condense those and move them up and chop off the end. That’s a classic editor move, right? You just take the last two paragraphs out of the piece, and you have the natural ending.”

➽ Bonus: In another story about the perspective of people facing rolling annihilation, Ismail Ibrahim writes about a Palestinian solidarity march in n+1.

Radiolab, “The Secret to a Long Life” by Sindhu Gnanasambandan: “Then there are moments like this, where I’m lying on my roof staring up at the beautiful sky on a perfect night and wondering how I have never done this before.”

Radiolab, “The Secret to a Long Life” by Sindhu Gnanasambandan: “Then there are moments like this, where I’m lying on my roof staring up at the beautiful sky on a perfect night and wondering how I have never done this before.”

“I know people say this happens, that time moves more quickly as we get older. But I’m really feeling it happening. I’m about to turn 30, and I feel like I’m going to wake up tomorrow, 80 years old, staring death right in the face,” Sindhu Gnanasambandan says near the start of this exceptionally good Radiolab episode. “It’s made me desperately want to know, is there something I can do to slow this down? Is there a way for me to make my life, this one, single life I have, is there a way for me to make it feel longer?” She sets off on a series of experiments, with the help of time perception researchers, but as she succeeds in lengthening how her days feel, the question morphs. Now, the episode asks, is a stretched time life worth the bother? “Having a life with a lot of novelty, change, with emotions will imprint more deeply in your memory,” one of the experts advises Gnanasambandan. “Then looking back at your last day, your last week, your last ten years, even, your lifetime, the longer subjectively, time stretches.”

So she devises an experiment to see how far time stretches. “For the next week, I’m gonna live the most novel life that I possibly can,” she tells Radiolab co-host Lulu Miller. “I have some rules: I’m going to wake up in a different bed every day. Not my own bed, a new bed. I will eat only things I’ve never eaten before. And outside of the non-negotiable things of being human, I will only do things I’ve never done before.” She volunteers at a soup kitchen, learns to skateboard, couchsurfs around New York, visits a New York State court, goes to a dating app mixer with her boyfriend, surfs with 12-year-olds without knowing how to swim, learns to paint with acrylics, learns to blow glass, attends a “performance art spa thing, it was just a lot of naked people and gongs,” goes on a solo road trip, sees the launch of a resupply ship to the International Space Station, and sees a supermoon.

It’s an exciting jumble of sounds, collected all over the Northeast, that’s bubbling with life. But eventually, Gnanasambandan admits she’s having a hard time processing the relentless novelty. “I think my whole system is just exhausted, the system that is just on high alert because everything is different all the time,” she says. Toward the end of the episode, she talks about a very unpleasant, emotionally taxing day that ended the experiment. The next day she meets with old friends at a Buddhist monastery that’s familiar territory. “This last day showed me I need days like that. I need comfortable, familiar days,” she says. “But now I know that those days are more likely to feel shorter — to get deleted.

Miller effectively pushes back on the basic premise. “I just question the value system. It’s only remembering the stuff where some expectation gets broken. Who decided? Evolution decided that the things that we’re going to remember, that we’re going to privilege, that are going to keep us awake, have to be novel, have to be breaking some rule, which to me, it just smacks of fear and self-preservation,” she says. “What if we could rebel against our master wirer, to also hold the little moments that normally get wiped?”

Marxist Poetry: The Making of The Battle of Algiers by Abbey Lustgarten and Kim Hendrickson: “Then there are moments like this, where I’m lying on my roof staring up at the beautiful sky on a perfect night and wondering how I have never done this before.”

Marxist Poetry: The Making of The Battle of Algiers by Abbey Lustgarten and Kim Hendrickson: “Then there are moments like this, where I’m lying on my roof staring up at the beautiful sky on a perfect night and wondering how I have never done this before.”

This documentary about the making of director Gillo Pontecorvo’s 1966 film The Battle of Algiers takes its title from a 1973 New Yorker essay by Pauline Kael. “The special genius of Pontecorvo as a Marxist filmmaker is that, though the masses are the hero, he has a feeling for the beauty and primitive terror in faces, and you’re made to care for the oppressed people — to think of them not as masses but as people,” she’d written. “Pontecorvo — the most dangerous kind of Marxist, a Marxist poet — shows us the raw strength of the oppressed, and the birth pangs of freedom.”

Pontecorvo’s manic search for faces that could capture that revolutionary moment was aided by his partnership with one of the leaders of the Algerian National Liberation Front, whose grinding victory against the French colonial government is the subject of the film. “Saadi Yacef, the Algerian co-producer, had such prestige and power that he could arrange almost everything,” he says in the documentary. “I prefer taking someone off the street, someone who’s never been in films, but who has the right face, over an actor with a face that isn’t quite right.” Yacef’s miracles included securing the temporary release of a convicted petty thief because he had a striking face, casting a man who’d been condemned to death as a man who shouts “Long live Algeria!” on his way to his execution, and, at Pontecorvo’s insistence, personally appearing in the film as his own revolutionary incarnation of recent years. “I told him I wasn’t an actor. I really did these things,” Yacef says. “He said I had a face that would be great for the film.” (He looked like Gary Cooper.)

The director explains that his story needed to reflect the cynical reality of French imperialists as well. “The imperialist enemy and class enemy of the Algerian National Liberation Front — the hyperintelligent French colonel played by Jean Martin — isn’t really a character; he represents the cool, inhuman manipulative power of imperialism versus the animal heat of the multitudes rushing toward us as they rise against their oppressors,” Kael wrote. “Yet it works, and brilliantly. The revolutionaries forming their pyramid of cells didn’t need to express revolutionary consciousness, because the French colonel was given such a full counterrevolutionary consciousness that he said it all for them.” Martin, otherwise best known as the first actor to play Lucky in Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, was no stranger to brutal absurdity. “I didn’t need to prepare to play a soldier, since I’d been a soldier myself in the French Liberation,” he says in the documentary. “I detest the military. I hate soldiers. And there’s nothing that interests me less than that world.”

Pontecorvo only really understood what he’d created as the score came together with the film. He worked with the composer Ennio Morricone, who had been the best man at his wedding and was fresh off Sergio Leone’s For a Few Dollars More. “The part of my work I like best is when I’m almost finished editing. I shut myself in with the Movieola and I start watching the film again and I whistle the musical themes I’d like to use,” he says. “That’s the moment when I truly begin to like the film.”