Paper Famine Hits Magazines

A pandemic-induced print shortage is upending press runs and sending titles scrambling to lock in supplies

Print is not dead yet, but it is in short supply. Literally. The pandemic’s general paper shortage, which has emptied shelves of toilet paper, paper towels, and diapers, has caught up with publishing, leaving some magazines scrambling to find enough paper to print on.

One publication hit particularly hard has been Texas Monthly, which, for what may be the first time ever in its history, could not print enough copies of its October issue to stock them on newsstands. “As a result of COVID-19-related shortages of paper and personnel at our printing plant, we were forced to reduce the number of copies that we printed for the October issue,” the magazine’s spokesperson Rachel Bryan Chinich said in a statement.

The staff at Texas Monthly, which calls itself “the National Magazine of Texas” and has traditionally fought far above its regional magazine weight class in National Magazine Awards and nominations, had to get creative just to print enough copies of the October issue to mail to subscribers, including, according to Chinich, “leveraging multiple printers.” In the end, they managed to get past that limited goal and are now celebrating what would have felt like a minor achievement before the pandemic. “We’re pleased to be able to fulfill our entire November run,” Chinich wrote.

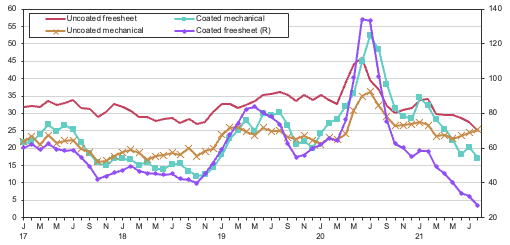

LSC Communications, Texas Monthly’s printer and one of the largest printing companies in the country, did not respond to requests for comment. In an August update on the paper market, the company noted that “coated paper supply continues to be lacking in North America, with limited availability from both domestic and overseas suppliers. Lead times and availability of products continue to pose a challenge for end-users.”

Paper producers’ inventories of coated freesheet and coated mechanical paper, both used by magazines, have plummeted since the beginning of the pandemic. Credit: LSC Communications.

“We’re hearing about the paper shortages,” said Abby Rapoport, publisher and co-founder of Stranger’s Guide, a travel magazine based in Austin which uses the same printer as Texas Monthly. “I’ve heard from LSC that they’re having to ration paper and not able to do full runs for some clients.”

Not everyone has been forced to reckon with such dire decisions. “We aren’t cutting page counts or limiting our runs,” said The Paris Review’s publishing manager Robin Jones. But most magazines have had to confront, in one form or another, the new scarcity. “While The Nation, like much of the industry, has had to navigate a market beset by recent paper shortages,” spokesperson Caitlin Graf said, “we have not—and have no plans to—veer off publication schedule for 2021 or 2022.”

There’s been particular concern about print’s increased precarity at Harper’s Magazine, where “Fuck the Internet” is something of a house motto. “We’re worried about it,” said spokesperson Giulia Melucci, but added, “our paper broker locked in paper for us, so we’re good until early next year, at least.”

This isn’t totally unprecedented. Following the influenza pandemic and the close of World War I, newspaper publishers were hit by what was known as a “paper famine.” In 1919, The Times-Independent of Utah went so far as to call it “a crisis that seems destined, unless relief comes from an unexpected source at the present time, to wipe many hundreds of both large and small papers out of existence within the next 90 days.” (The paper survives.) To free itself from the vagaries of the global paper supply, in the following decade, The New York Times invested in building an entire paper mill town deep in the forests of Ontario whose population grew to 5,000 by 1951. (The Times sold its interest in 1990.) Then in 1973, as the American economy teetered, paper ran extremely short again.

This isn’t totally unprecedented. Following the influenza pandemic and the close of World War I, newspaper publishers were hit by what was known as a “paper famine.” In 1919, The Times-Independent of Utah went so far as to call it “a crisis that seems destined, unless relief comes from an unexpected source at the present time, to wipe many hundreds of both large and small papers out of existence within the next 90 days.” (The paper survives.) To free itself from the vagaries of the global paper supply, in the following decade, The New York Times invested in building an entire paper mill town deep in the forests of Ontario whose population grew to 5,000 by 1951. (The Times sold its interest in 1990.) Then in 1973, as the American economy teetered, paper ran extremely short again.

But those previous shortages happened in an era when print publishing was still relatively robust. Today’s existential crisis of print goes deeper than the availability of paper.