The Smiths’ Challenge: A Great Ad Sales Pitch in Search of an Editorial Product

Justin Smith and Ben Smith’s announcement brings back memories of the promise — and pitfalls — of an earlier global media startup. Plus: a digest of our best reporting from the last week.

Welcome to The Fine Print’s free weekly digest! If you’d like to get this emailed to your inbox every week, please sign up here.

The new year started out for me with a strong sense of déjà vu when Justin Smith, CEO of the Bloomberg Media group, announced he was stepping down to launch a new media company with soon-to-be-former New York Times media columnist Ben Smith. For much of 2014, I worked closely with Justin as a consultant at Bloomberg as he fashioned a digital strategy for the consumer-facing division of a company that had up to then been laser-focused on its lucrative terminal business. But where I got to know him best was more than a decade ago when he was the president of the Atlantic Media Company and a champion of The Atlantic Wire, a news site spin-off of the magazine I edited that was shuttered not long after he (and I) departed. Another big digital initiative at the time — which would, much to my chagrin, hoover up most of Atlantic Media’s capacity to invest in expansion — was the business site Quartz, which was largely Justin’s brainchild.

When it started in 2012, Quartz and The Atlantic Wire shared the same small, bare office on Spring Street in SoHo (my wife and I assembled the first Ikea desks one Saturday afternoon), and while I was never directly involved in Quartz, I got to listen in on a lot of early strategy talk and was occasionally pulled into the sole conference room when big decisions were being mulled. One memorable discussion was about whether they should brand as “Quartz” or “QZ” to match the sexy qz.com domain they’d recently acquired.

So, I heard a lot of distant echoes when Justin wrote that he was inspired to launch his new venture “Project Coda” when he “realized that a new cohort of global, digitally-native, educated news consumers had emerged that were poorly served by legacy news media.” He doesn’t say it’s a recent realization; the origins he offers go back to his 1991 internship at the Paris offices of the International Herald Tribune. This time this insight seems to have been distilled into a kind of mantra repeated by former Atlantic Media owner David Bradley (who looks like a likely investor) in The Wall Street Journal and by Ben who told his soon-to-be-ex-employer, “There are 200 million people who are college-educated, who read in English, but who no one is really treating like an audience, but who talk to each other and talk to us.”

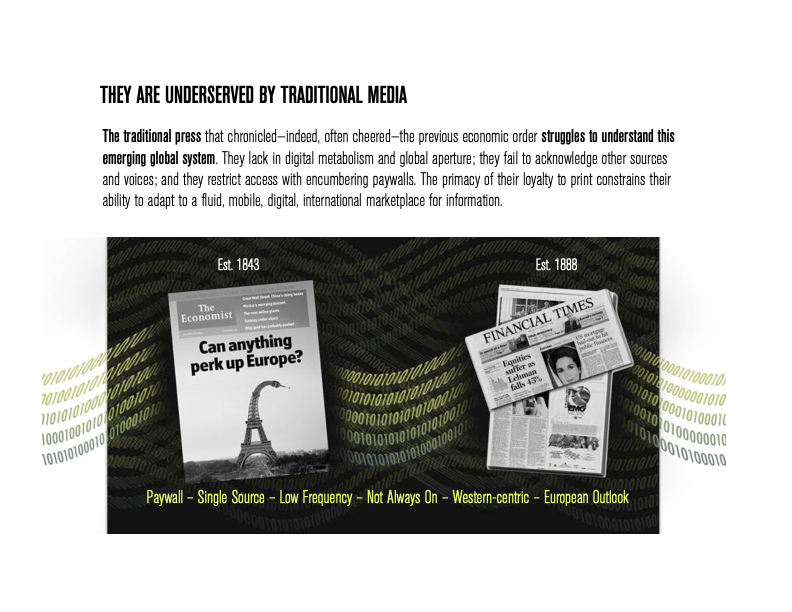

That idea of an underserved elite audience has inspired a fair amount of guffawing, but it was also a key part of the pitch for Quartz. Amidst my digital clutter, I found an early deck (so early, that the graphic designers had barely gotten their hands on it) prepared for a sponsorship meeting with a big corporate advertiser that leaned hard into the same themes (the word “global” appears on nearly every slide). “An elite class of digitally savvy, information-hungry post-national business leaders have emerged from and shape this new global economic order,” read one slide. The next slide was headlined “They Are Underserved by Traditional Media” and over a graphic showing The Economist and the Financial Times, argued, “The traditional press that chronicled—indeed, often cheered—the previous economic order struggles to understand this emerging global system. They lack in digital metabolism and global aperture.”

Quartz has been ahead of its times in a number of ways, most notably in embracing mobile-first site design and being quick to find creative journalistic uses for new technology. I was wowed when they figured out how to report on Davos by using antennas to track private helicopter traffic. And it once went pretty much all-in on becoming a chat-based app. But even though it’s published a lot of high-quality journalism, Quartz never exactly reinvented news or threatened to displace the legacy institutions with global news-gathering footprints. That Quartz, which was bought out from its prior owner Uzabase in 2020 by its CEO Zach Seward and editor-in-chief Katherine Bell, has survived as long as it has, I’d argue, owes some large part to Justin’s original pitch, which pre-launch landed four blue-chip sponsors who, if memory serves, each made multimillion-dollar commitments.

No one should be faulted for trying what worked before, and my gut is that Justin will be able to do the same thing for “Project Coda.” Another early denizen of that Spring Street office, Gideon Lichfield, who had joined from The Economist as Quartz’s global news editor, is leading a similar project at Condé Nast, where, as the new global editorial director of Wired, he’s relaunching the title by combining the U.S. and U.K. editions into one English-language newsroom. (In November, Andrew Fedorov filed a great report on how the reshuffle fits in with Condé’s new global strategy.) It keeps working because, if you’re a marketer trying to reach a target audience of rich professionals in Singapore, Dubai, Nairobi, and São Paulo, it would be very compelling to reach them via a single media brand. I don’t have any doubt that Justin will be able to sell deep-pocketed sponsors on this vision. But it does leave Ben with a hairy problem: an ad sales pitch in search of an editorial product.

The trouble is that those “English-speaking, college-educated, professional class of over 200 million people,” as Justin’s memo puts it, are primarily similar because they use the same technology, financial, and entertainment products, and that similarity accounts for only a small sliver of anyone’s interests, many of which are still mostly local, like politics, sports, weather, schools, and traffic. While that stuff is not where great fortunes are made in media these days, it will be very difficult for a media outlet whose heights of cultural relevance are the new iPhone, the HBO show of the moment, and whatever’s trending on TikTok to become someone’s primary source of news without also serving some of these more parochial concerns. The bigger risk is that an all-out quest to optimize content for global relevance becomes a prod towards the lowest common denominator.

The reason you hear bandied about most frequently for why media brands have a less-than-global footprint is usually about a geographic reference in their title: New York spun up Vulture and The Cut because they concluded “New York” turns too many people off. Similar theories are offered for why The New York Times and BBC haven’t built global businesses to match their global prestige. At The New York Times, in particular, the quest to find English-speaking subscribers outside of the U.S. has turned into an A.I.-powered search for needles in a haystack, along with hefty discounting.

Another common reason you hear for what’s holding back a new entrant in the global news space is antiquated formats. One of the few answers about editorial plans that Ben gave to The New Yorker’s Clare Malone was, “I don’t think that newspaper articles or magazine articles are, for most stories, most days, the best way to deliver the news.” But coming up with a completely new format is a rather high bar for any editor, even one with the impressive track record he has, to clear successfully.

The Way The New York Times Won Its Slack Back

‘EMOJIS ARE BASICALLY THE ONLY WAYS THAT EMPLOYEES CAN INTERACT’

By Andrew Fedorov

The New York Times culture extends well beyond the bounds of their internal communication platforms, but a potential harbinger of how the company might intend to tackle its various inner tensions and fault lines is the way in which they’ve tamed their company Slack. While the periodic outrage cycles buffeting The Times newsroom have been varied, its Slack has been a recurring character. The first big crackdown came on January 27, 2021, when a memo headlined “Communicating with one another” went to every Times employee. Signed by deputy managing editor Carolyn Ryan and chief marketing officer David Rubin, it announced that the #newsroom-feedback channel would be archived and replaced with a set of read-only channels as well as an #ask-the-editors channel where staff could submit questions for the standards department to address. Union leaders have called the all-newsroom replacement along with the all-company channel “one-way channels” and characterized them as forums for management to spread their positions on issues like the Wirecutter strike without allowing the sorts of responses from employees that leaked out of the #newsroom-feedback channel. Some senior reporters argue that most of the discontent in Slack comes from a relatively small and particularly vocal group. They see the new channels as part of a more significant, long-delayed trend of making it clear to an influx of new employees who have joined the paper in the last few years that it’s time for them to get in line with older Timesian values… >> READ THE REST

On the Front Lines of an Insurrection

‘I KEPT REASSURING VISITORS THAT THE CAPITOL WAS IMPENETRABLE. I WAS WRONG.’

By Sara Krolewski

“We aren’t war correspondents,” noted Punchbowl, a newsletter for D.C. insiders, in its reflection on the one-year anniversary of the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol. One year ago, dozens of journalists gathered for what most believed would be a contentious but fairly manageable day of protests against Joe Biden’s formal confirmation to the Presidency. By the end of the day, that assumption had been completely upended. In storming the Capitol, the Trump-led insurrectionists left behind a trail of destruction that included mangled cameras, stolen equipment, and injured reporters, some forced to don gas masks and riot gear. In effect, the Capitol became the new front lines of a war zone that has peppered the country in recent years and produced a kind of domestic war correspondent: journalists in the field working doggedly, often putting themselves in significant danger, to cover a rising tide of extremist violence. The moment on January 6, 2021, when Megan Pratz, the political director of Cheddar News, realized she was about to witness an unprecedented news event came just after she entered the Capitol building to watch senators proceed into the Senate chamber to ratify the results of the 2020 election. As the politicians disappeared, a Capitol police officer came sprinting down the corridor, seemingly out of nowhere. When Pratz and her colleague, photojournalist Shawn Klein, turned to leave the building, guards informed them that the Capitol had been locked down. Pratz recalled that she was called “the C-word” by an enraged member of the mob who spotted her recording and that other members yelled out, “We’re coming for you!”… >> READ THE REST

Our A.G. AI 3000 was just as shocked as The New York Times masthead to learn that Ben Smith was departing the paper. The perennial longshot becomes the first scratch in The Fine Print’s odds table on who will replace Dean Baquet as executive editor. While the long odds on Smith attracted some of our pool’s more adventurous wagerers, rules are rules: a scratch is counted as a loss, and those bettors forfeit the OTR$ bucks they placed on him. Our quants have been busy feeding their algorithm a steady stream of Times internal chatter and other proprietary data to produce the first set of new odds since before the holidays. As the months roll on, the certainty among Times staffers and outside speculators that Joe Kahn (+150 ▲50) will be the new boss has not abated. While early on the pool seemed to be seeking out a suitable not-Kahn contender to rally behind, the absence of a clear alternative has only strengthened Kahn’s lock at the top of the table and shortened his odds. But an interesting race within the race has emerged: if Kahn is looking like a lock, who will be his new right hand as managing editor? A.G. AI 3000’s emerging favorite is Carolyn Ryan (+500 ▲250), whose prominence in thorny management problems like the Times’s Slack crackdown and the sudden departure of Smith (who she edited) has shortened her odds. It’s looking more and more like the top post is Kahn’s to lose — but if Ryan is looking like the most likely No. 2, that puts her a touch closer to the job than the other non-Kahn contenders, deputy managing editor Cliff Levy (+750) and assistant managing editor Marc Lacey (+750). … >> READ THE REST

Who Wants to Be the Next New York Times Media Columnist?

By Andrew Fedorov

When The New York Times announced on Wednesday that media columnist Ben Smith was leaving his job to start a new global news organization with also-resigning Bloomberg Media CEO Justin Smith (no relation), questions began burbling about who would take on one of the most prominent roles in American media reporting next. The column rose to prominence after David Carr launched it as The Media Equation. After Carr died in 2015, the column was rechristened the Mediator under Jim Rutenberg in 2016, but its prominence ebbed as he focused on investigative work around Donald Trump’s dealings with the tabloid media. But Smith brought it back with a fury after he left his job as editor-in-chief of BuzzFeed News to take on the column, re-dubbed The Media Equation, in January 2020, delivering a run of scoops, from the story that took down Ozy to the revelation that Harper’s brought its staff back to the office at the height of the pandemic. While there’s no indication The Times is in any hurry to find a replacement, the first question among the media-savvy readers who lapped up such scoops was: Who’s next? Whoever takes on the column will have big shoes to fill but will also have to take it in their own direction. It’s also difficult to overlook that, so far, the only authors of the column have been white men. Many names have been bandied about, and, to sort out the fantastical from the realistic, The Fine Print talked with a few potential columnists to ask if they’d be interested in the job and what they think the future of the Times media column should look like.… >> READ THE REST