The Influential Rise and Fated Fall of Entertainment Weekly

How a magazine that pre-dated video streaming, smartphones, and the internet helped create an entertainment media landscape where it could no longer survive

When Jeff Jarvis, then the “Picks and Pans” columnist for People, first wrote his proposal in 1984 for the magazine that would become Entertainment Weekly, there was no TikTok, no Disney+, no Netflix, no iPhones, no DVDs, no broadband home internet. But there was TV, and he had an idea for what TV viewers needed: “Today, there is simply too much to choose from,” Jarvis wrote in his memo. (It would be another eight years before Bruce Springsteen would release his song “57 Channels (And Nothin’ On)” in 1992.) “The magazine would appeal to baby boomers and yuppies,” he went on, “ones with a lot of money and a little time to spare.” But there was something common back then that one seldom sees in 2022: the office water cooler. Giving people something to talk about when they encountered each other — in person, of course — became EW’s raison d’être for the editors who cranked out issues week after week following the title’s launch in 1989. “EW really nurtured and made the water cooler conversation mainstream,” said Josh Wolk, a former senior editor who worked at the magazine from 1997 to 2009, “and got entertainment lovers to be able to seize on what pop culture fans were interested in.”

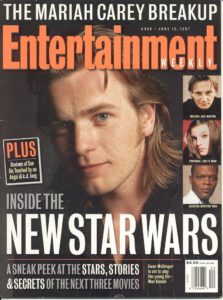

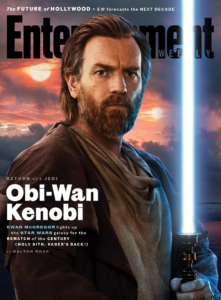

Entertainment Weekly’s final print edition will hit newsstands this Friday, March 18. The cover for the April 2022 edition — it has been published monthly since 2019 — is fittingly nostalgic. It shows Ewan McGregor preparing to return in an upcoming Disney+ series as Obi-Wan Kenobi, a role he has been playing since his casting was first announced on the cover of EW in 1997. On February 9, DotDash Meredith announced it would end the print production of six of the magazines it had acquired from Meredith Corp., which had, in turn, acquired EW’s original publisher, Time Inc. All in all, the decision to turn EW, InStyle, Health, Eating Well, Parents, and People en Español into digital-only brands led to about 200 people losing their jobs. (Entertainment Weekly did not respond to requests for comment.)

While the move was another gut punch to the print industry, it was not entirely unexpected. Entertainment Weekly has struggled to find an identity for quite some time now. As online streaming and full-season binging replaced movie theaters and live television, so, too, went the synchronous office gossip and live-tweeting of episodes as they premiered on television. Still, for many people born in that awkward period between millennials and Gen Z, EW was the benchmark for pop culture. This reporter vividly remembers receiving the July 8/15, 2011 issue in the mail while away at summer camp. In honor of the eighth and final Harry Potter film, a Sorcerer’s Stone-era Daniel Radcliffe beamed over a light blue background with white and yellow type that read: “Thank You, Harry!” It was a bittersweet, gone-but-not-quite-goodbye moment, not unlike how the veterans of EW feel about the end of the magazine’s print run.

“I don’t think this was a surprise to anyone who knew anything about EW or who had followed its history,” said Mark Harris, who joined as a columnist in 1989 and eventually rose to be its executive editor. “But that didn’t mean that we weren’t all still — you know, many of us — very sad.”

Harris wrote EW’s origin story for the magazine in 2015. (Another history was written by Anne Helen Petersen for The Awl, which received a response by Jarvis, who left the magazine within a year of its first issue.) His opening was intended as a testament to EW’s perseverance and dogged determination, but now, it reads as more of an omen: “‘Let me tell you why you’re doomed.’” The piece recounts a conversation Harris had with a “longtime magazine editor” three months before launch: “‘You’re doomed because nobody cares. People like movies. People like TV. But they don’t want to know how it’s made. They don’t want to talk about it. They don’t want to read about it. And they don’t want to think about it. I give you six months.’” Harris laughed when The Fine Print read back his own lede. “We really outlived expectations: We outlived that prediction, we outlived the company that employed the man that made that prediction, and we outlived — by the way — the man who made that prediction,” he said.

Looking back with nearly 40 years of hindsight, Jarvis, now the director of the Tow-Knight Center for Entrepreneurial Journalism at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY, sees the roots of EW’s undoing in the “abundance of choice,” as he puts it, that was his original inspiration. “What I learned as a critic through the years was that having more choice led to more competition led to more quality. It was counterintuitive as hell,” Jarvis said. “If TV is already shit, more TV should be more shit. It was the opposite. So I don’t think anybody understood that rule of abundance when it came to entertainment.”

The biggest challenge to EW’s cultural relevance, Jarvis said, was the internet’s favorite critic: Rotten Tomatoes. “We can all go to our friends, we can read 200 reviews on Amazon, we can find our own water level of the culture and find what we like,” Jarvis explained. “The conceit of a mass-market magazine, of course, is that it’s one voice for all. Well, that’s what was wrong. It was right for the time because it’s what we had.” With the internet, the entertainment industry has bombarded its consumers with more choices than Jarvis envisioned back in 1984. But those same technologies made critics less needed, not more. “The people formerly known as the audience are now the critics,” he said. “How do you capture their views and their voice?”

“When everybody’s watching something at different times — including going back and rediscovering New Girl, then it makes it all the more difficult to figure out what the water cooler conversation is like,” said Wolk, who was the first staff writer hired exclusively for the ew.com web site.

“Even before I left the magazine,” Harris said, “it was very clear that the advent of the internet was changing everything, and changing everything in ways that many people in management at legacy magazines were just not well-equipped to predict or to keep up with.” Over the years, he said, EW tried nearly every possible combination of online and print publishing schemes: “Should we put the entire magazine up on the site? Should we put none of the magazine up on the site? Should the site be primarily a vehicle to promote the print magazine? Should the site only have bonus content that you can’t get anywhere else?”

And yet, in all those changes, the magnitude of the shift in the entertainment and media landscape due to the internet never sunk in. “The realization that this thing was going to eat us never quite took hold,” he said. “You can’t take a bunch of people who’ve worked in print all their lives, and expect them to realize that, like, ‘Oh, this new thing that we think we’re controlling, is actually controlling us, and will eventually kill us.’”

Not to say there was not a sense of panic — particularly after the 2008 financial crisis. “Like every magazine, we were doing an audible gulp. That’s when the writing started to be on the wall,” Wolk said. “I remember having these conversations realizing, for most magazines, it’s like, ‘Right now, it’s about managing the decline,’” he said. “That wasn’t an EW problem — that’s a print problem.”

While there is no shortage of content about entertainment pushed across various digital platforms these days — at outlets like Vulture, Refinery29, Variety, The Hollywood Reporter, and, of course, the continuing ew.com — many of their tactics trace back to EW’s approach to entertainment as a spectator sport and not simply a spectacle. The common challenge is keeping up with the increasing pace at which audiences consume entertainment.

Less than ten years ago, EW was struggling to keep up on a weekly basis. (In his proposal, Jarvis was adamant that the publication should be a weekly, not a monthly, because it was impossible to know what people would be watching over the course of a month — even in the 1980s.) “Let’s say a big Breaking Bad episode is airing,” Wolk said. “The websites would get a screener early, they would say, ‘Oh my god, this is the big thing that happens. Everyone’s gonna be talking about it. Everybody’s gonna want to know. Everybody’s gonna be talking about that at 11:01 as soon as it airs. Let’s talk to Vince Gilligan and get him to dissect the episode and talk about it,’” he said. “So the second it’s over, we make this go live and everybody gets instant gratification to dig into this stuff. That really sort of hurts print magazines.”

But fast forward to 2022: The rules have changed, and the show is Inventing Anna. “What people want now from Inventing Anna is a take on Anna Delvey’s clothes,” Harris said, “and some piece about how individual episodes of mini series are too long, and what Inventing Annagot right and wrong about magazines, and a deep dive on Julia Garner’s accent. And they want that all instantly — possibly while they’re watching the show.”

In that sense, EW gave rise to some of the same forces that would eventually render a weekly entertainment magazine obsolete. “I’ve watched how entertainment news and coverage has really gravitated online,” said Wolk, who since leaving EW has led digital outlets including Yahoo Entertainment and Vulture. “It seemed harder and harder to imagine a world in which somebody would keep EW going.”

“I think it was of the time,” Jarvis said. “It was of the beginning of the increase in choice and abundance. So it was meant for that time, and it did that job. But that time was limited, once the web came along. It should have bought Rotten Tomatoes.”